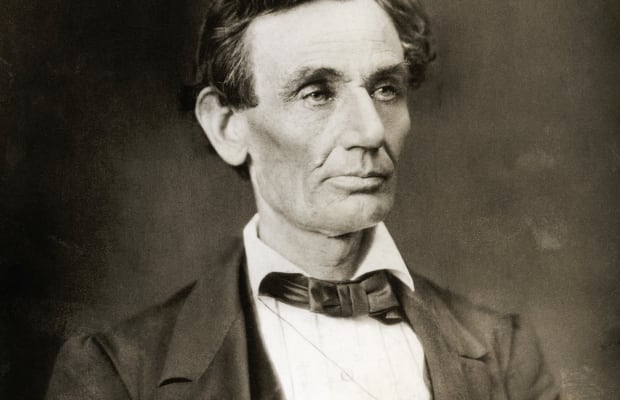

I’ve always wondered what it must have been like to be alive in 1860 and experience the American election that created Abraham Lincoln, insured the secession of 11 southern states and spawned the deadliest war in the nation’s history.

Lincoln won only 40% of the popular vote in that election – and almost no votes in southern states – and to many of his fellow countrymen the mere thought of his election was cause for panic and eventually dissolution. One side was trying, in the face of enormous odds, to preserve the Union. Another side was willing to risk civil war.

This week we all have a better sense of what it must have been like to be alive in 1860. The United States – I hope I’m wrong here – seems to be tottering at a dangerous place we’ve not seen in our lifetimes, or perhaps even in our great grandparents’ lifetimes. Maybe, in fact, not since Lincoln and 1860.

The election of 2020, the election we have been preparing to endure for four long years, may only prove one thing: America is even more divided than we imagined.

I have to admit I am nostalgic for, if not an entirely better more gentle political time, at least a time with better political expectations, a time when there was still a middle in American politics, a time when we were not just divided tribes. One such time, ironically, was the tumultuous 1960’s, a decade dominated by fights over civil rights, including the murder of the leader of the civil rights movement. The 1960’s where in many ways an ugly time: presidential assassination, campus unrest, urban riots and a senseless war.

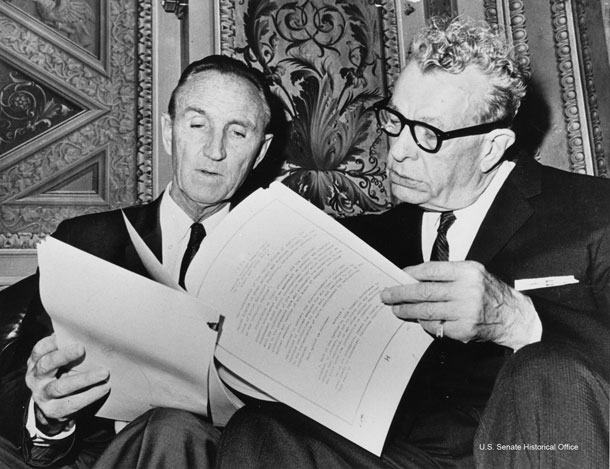

Yet, against all the odds, many of the nation’s best political leaders, Republicans and Democrats, were equal to the decade’s enormous challenges. The success of American politics in the 1960’s owes much to two partisan politicians who in style and substance could not have been more different. The story of Mike Mansfield of Montana and Everett Dirksen of Illinois, the Senate majority and minority leaders, may seem quaint, even unrecognizable in our divided America of 2020. But it is instructive.

Mansfield was a New York-born orphan, packed off to Butte, Montana as a youngster to live with relatives. He hated it. Ran away from what passed for home and ended up doing the nastiest work in the copper mines of the richest hill on earth. Dirksen grew up on a farm outside of Pekin, a town in central Illinois. His Protestant parents were German immigrants. Mansfield’s immigrant roots were Irish-Catholic. Both men served in the Great War and both struggled to gain a higher education. Mansfield’s wife insisted he get a degree and he eventually earned a master’s and taught history. Dirksen sold books and magazines door-to-door to finance his law degree.

Dirksen was voluble. One reporter called him “the Wizard of Ooze.” The label stuck because it was true. Mansfield was laconic, given to one-word answers – “yup” and “nope.” It’s often said the most dangerous place in Washington, D.C. is the space between a politician and a television camera, but Mansfield, even at the height of his power as majority leader, a tenure that lasted for 16 years, shunned the spotlight. Imagine such a thing.

The political and personal paths of these two remarkable Americans crossed in the United States Senate where they helped civilize our politics and make the place work.

Among many enduring bipartisan accomplishments Mansfield and Dirksen led the Senate and their respective parties to pass of the historic Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, they passed Medicare and created the public broadcasting system. They worked with presidents of both parties. It’s how politics once worked.

One story exemplifies how the copper miner from Montana cooperated with the magazine salesman from Illinois. In 1963, Democratic President John Kennedy had negotiated a limited nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union. Kennedy saw the treaty, particularly after the Cuban missile crisis a year earlier, as a step back from an unthinkable nuclear Armageddon. Dirksen, a conservative Republican on foreign policy issues and a man deeply suspicious of the Communist regime in Moscow, was not entirely convinced a treaty was in the nation’s interest. Mansfield insisted he speak directly with Kennedy and the two leaders went to the White House to, well, make a deal.

During the ensuing conversation – we know it lasted 33 minutes because it was captured on a White House recording – Kennedy suggested that Dirksen put his reservations in writing, which he had already done. “I hope you don’t mind that this is a little presumptuous on my part,” Dirksen said, as he proceeded to read aloud a copy that he produced from his suit pocket. Dirksen’s draft became the letter Kennedy sent to the Senate.

Dirksen then counseled the Democratic president on how to handle Senate opposition from his own party, while explaining that he could convince enough of his fellow Republicans to get the necessary two-thirds vote to ratify the treaty.

It wasn’t known until years later when the recording of the meeting became public that the two partisan Senate leaders worked together to help the American president accomplish something that he likely could never have done without their unselfish, non-partisan assistance. The test ban treaty approved by the Senate in 1963 became the foundation of every subsequent nuclear weapons treaty. Kennedy considered it among his greatest, if not the greatest, domestic accomplishments.

The basic decency and fair play of Dirksen, Mansfield and Kennedy that is on display in this little story, particularly given our current toxic partisanship, is nothing short of stunning. We struggle ahead as Americans. Yes, we really do have a shared stake in the future of a country that is not just about seeing that our side wins. If there are Dirksens and Mansfields among us, this is their moment.

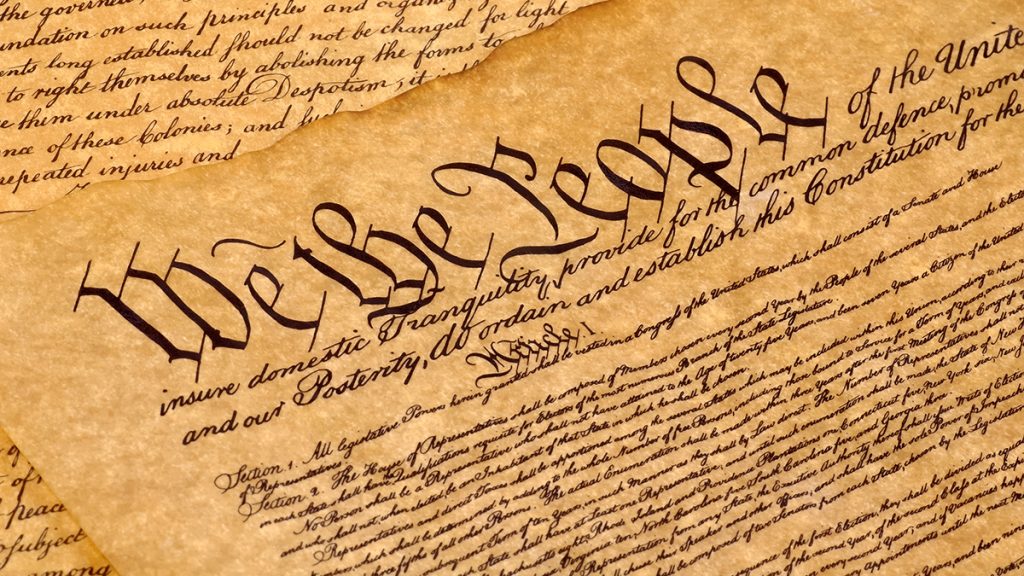

As Lincoln said in his Second Inaugural Address in March, 1865, while the Civil War still raged: “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.”

Come on America, we used to believe we were all in this together. Every one of us needs to figure out how we can be one country again. Either we revive the spirit of politicians like Dirksen and Mansfield or we are doomed.

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

A couple of stories you may find of interest…

Counties with worst virus surges overwhelmingly voted Trump

This is a remarkable example of taking an obvious story – the expanding coronavirus in the United States – and examining the why.

“An Associated Press analysis reveals that in 376 counties with the highest number of new cases per capita, the overwhelming majority — 93% of those counties — went for Trump, a rate above other less severely hit areas.

“Most were rural counties in Montana, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa and Wisconsin — the kinds of areas that often have lower rates of adherence to social distancing, mask-wearing and other public health measures, and have been a focal point for much of the latest surge in cases.”

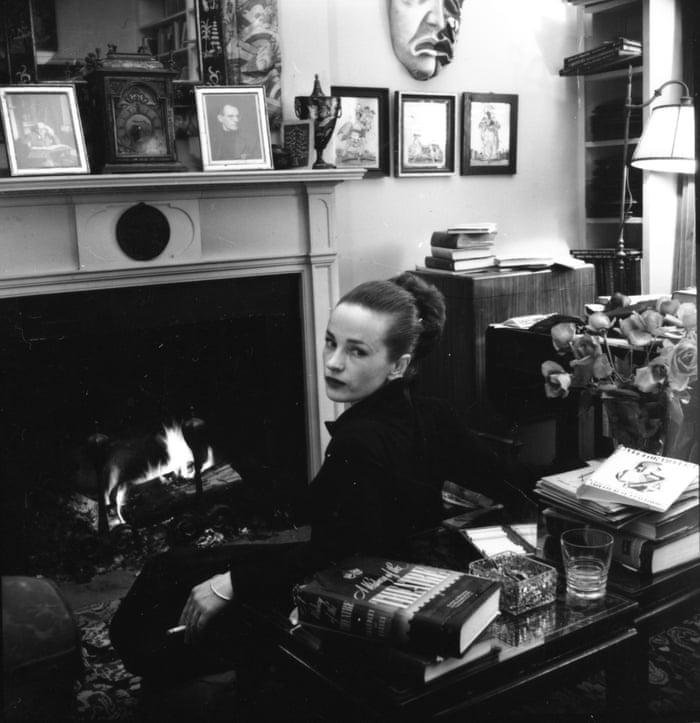

Helena Bonham Carter

I’ve been receiving – and reading – a daily email from the Irish Times since I fell in love the newspaper during a trip to Ireland some years ago. It never fails to give me something really interesting, including this feature on the actress who plays Princess Margaret in The Crown, starting again soon on Netflix.

“[Helena Bonham Carter] spent months on her research. She wasn’t interested in anything that made the princess sound like a cartoonish snob, but looked instead for nuances. ‘I’m not disputing that Margaret was rude, but often the reason people attack others is because they feel vulnerable,’ she says. To locate that vulnerability, she interviewed Margaret’s surviving friends, including her former lady-in-waiting, Anne Glenconner. ‘I’ve always been a swot. Honestly, you should see my Margaret file. Tim used to look at all my files and say, ‘You’re not an academic, you’re a flipping actor.’ But I have to suspend my own disbelief before I ask anyone else to suspend theirs. And it’s such an outrageous ask: I have to pretend to be Princess f**king Margaret?’ she says, her voice rising.”

A great feature about a wonderful actress.

Thanks for reading. Stay safe…and please do what you can to strengthen our democracy.