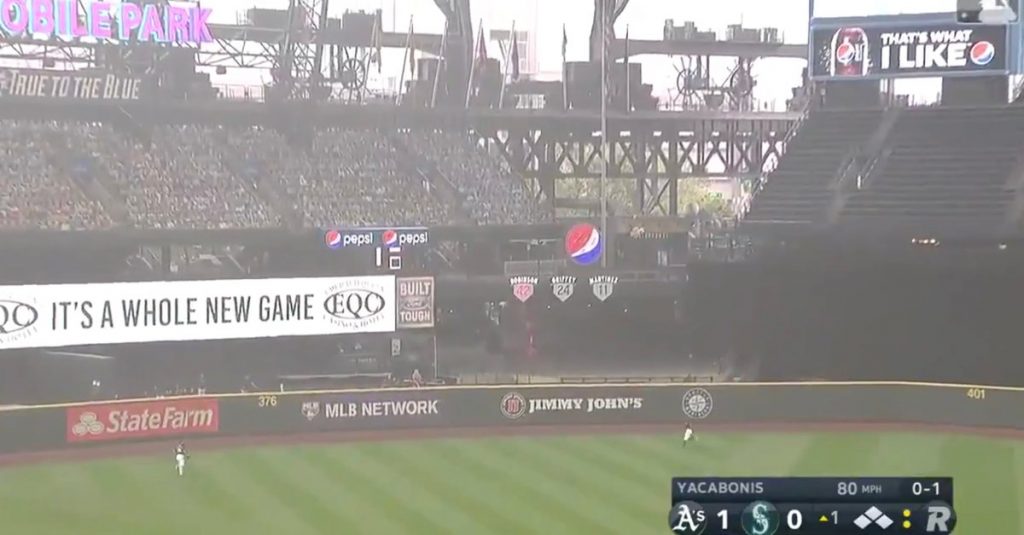

If you could choose just one moment from the last week to capture the utter unreality of our time – and our politics – you could do worse than looking at the highlights of a baseball game played last Monday in Seattle.

The A’s and Mariners split a doubleheader, but the images that linger from the game have nothing to do with home runs or great defensive plays. The dystopian scene that persists is the reality that the game was played in an empty stadium where seats were filled with smiling cardboard cutouts not fans, with many players wearing face masks and wondering why the games had been played at all.

“I think it was OK breathing, but we definitely noticed it,” Mariners centerfielder Kyle Lewis told reporters. “The sky was all foggy and smoky; it definitely wasn’t a normal situation, definitely a little weird.” True statement.

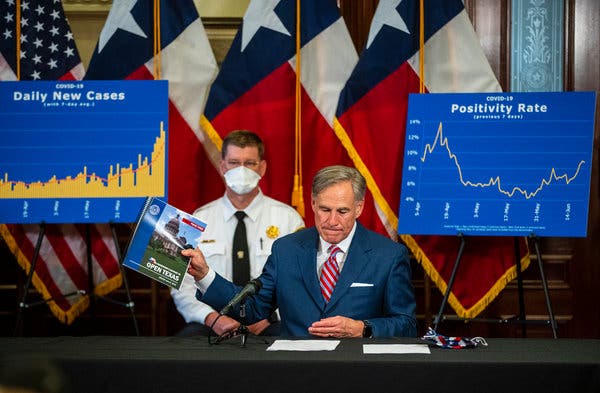

The Seattle skyline – and every skyline from L.A. to Missoula – was obscured by a mile’s high worth of smoke. The air quality this week in four major western cities is among the worst in the world, all brought to the Seattle ballpark and your lungs by the catastrophic wildfires raging from southern California to the Canadian border, from the Oregon coast to Montana.

The West is burning. The pandemic is raging. The climate is cooking. And a sizable percentage of Americans are willingly suspending their disbelief about all of it, still enthralled with the smash mouth nonsense of the biggest science denier since Pope Urban VIII in the 17th Century decreed that Galileo was wrong and the Sun really does orbit the Earth.

The suspension of disbelief, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote in 1817, is a necessary element of fiction, or perhaps more pleasingly, poetry. It demands, Coleridge said, that we “transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.”

You have to want to do this suspension of reality business since it really doesn’t come naturally. A reflective human reaction to things that just don’t seem true is to question what you hear or see. Not anymore. We have reached our “Duck Soup” moment and we are living the line delivered by Chico, one of the Marx Brothers in that 1933 movie: “Well, who ya gonna believe me or your own eyes?”

When told by the secretary of the California Natural Resources department, Wayne Crowfoot, that the record three million acres burned so far this year in that state required a response that goes beyond managing vegetation, the president of the United States blithely mumbled: “It’ll start getting cooler. You just watch.”

Crowfoot pushed back gently on the science-denier-in-chief saying, “I wish science agreed with you.” But like the surly guy who has to win every argument at the neighborhood bar – back when the neighborhood bar was open – Donald Trump said, “I don’t think science knows actually.”

Undoubtedly, his many supporters celebrated more of their “poetic faith” even though every eighth grader in the American West knows more about forests and fire than our president from Queens, the same guy who predicted repeatedly that the virus would “just go away.”

To hear the president on the campaign trail, cheered on by nearly every one of the intellectually bankrupt elected officials in the Republican Party, the pandemic is over, the economy is roaring back and radical thugs are coming to a suburb near you. Reality that doesn’t depend on suspending disbelief would be, as James Fallows wrote this week in The Atlantic, that “Trump is running on a falsified vision of America, and hoping he can make enough people believe it to win.”

The Trump campaign flew into Nevada a few days ago to rally with hundreds of supporters packed shoulder to shoulder in a building in Henderson. The event took place in defiance of not only the state of Nevada’s prohibition against such large gatherings, but the clear guidance of Trump’s own science and medical experts. But, then again, they are all probably “elitists” from liberal colleges and universities. What do they know?

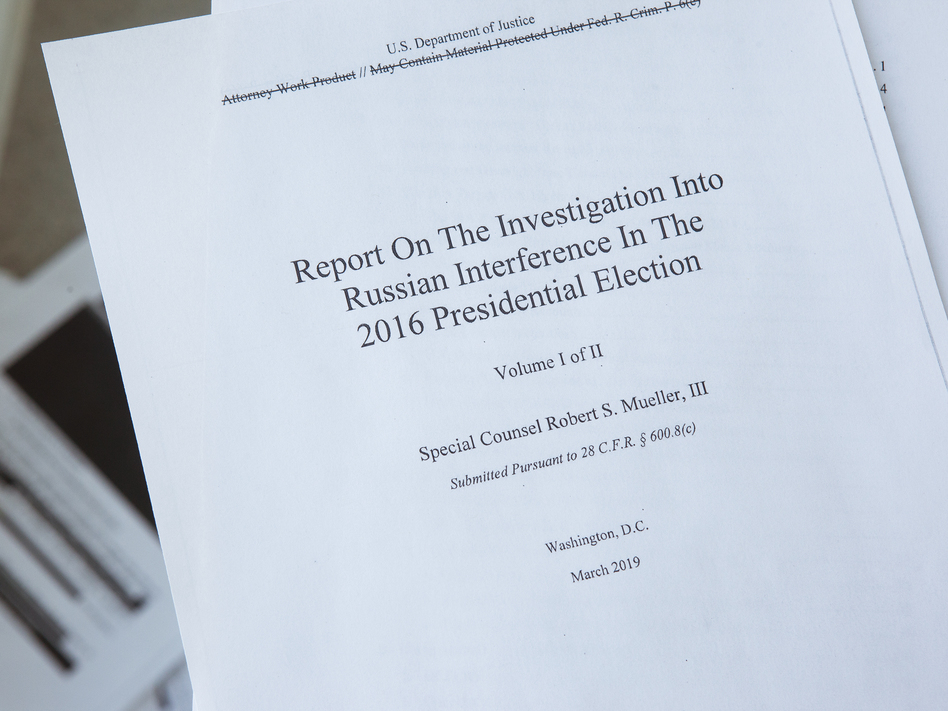

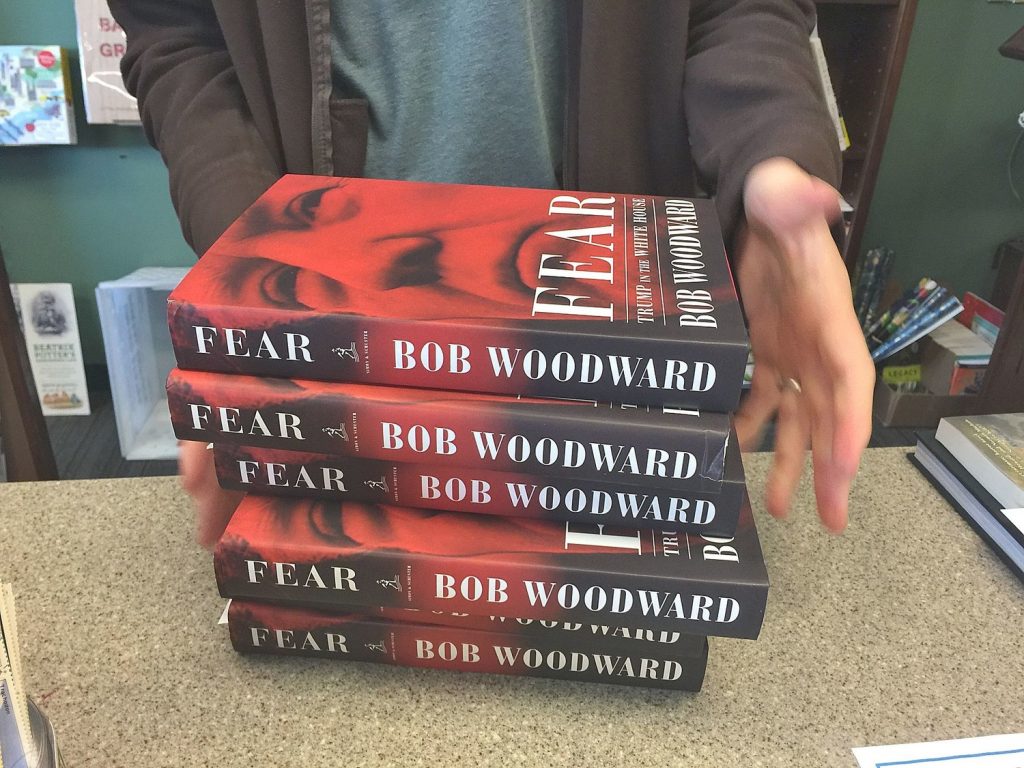

The Nevada rally and subsequent campaign events in Arizona and elsewhere came at the same time as the release of Bob Woodward’s latest book, in many ways, like all Woodward books, a Washington insiders’ version of the presidency as a decades long exercise in suspended disbelief. There is, however, one thing different about this Woodward book. He’s got the tapes.

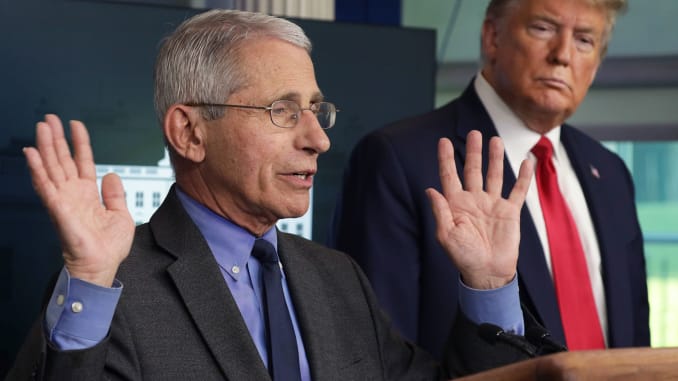

Back in the spring when Trump was daily trying to happy talk his way through the pandemic he said on April 10: “The invisible enemy will soon be in full retreat.” Three days later he spoke by phone with Woodward who recorded the conversation with Trump’s full knowledge and confirmed that he had been lying to all of us for weeks. “This thing is a killer if it gets you,” Trump said on April 13, “if you’re the wrong person, you don’t have a chance.” Trump went on to call the virus that once was magically “just going to go away” a “plague.”

In an earlier interview with Woodward in February Trump called the virus “deadly stuff” that was “more deadly than your, you know, your — even your strenuous flus.”

At least two things are happening here. Trump was caught in real time lying about a pandemic that will soon have claimed 200,000 American lives, shutdown schools and businesses and devastated the economy in ways we can’t yet imagine. By his ignorance and malevolence, the president, and those most guilty of aiding his mission of chaos and death – read congressional Republicans – continues to wreak havoc on every single one of his constituents. It should go without saying that it didn’t have to happen, and it hasn’t happened in most of the rest of the world. You can look it up.

Second, the president and his pathetically craven enablers are waging a massive propaganda campaign in an effort to win an election, relying on huge doses of magical thinking larded with suspended disbelief.

So, sure, Trump’s doing a superb job. It’s going to get cooler and magically that smoke once it’s gone will never reappear. The “deadly stuff” is nothing to fret about. I mean, after all, who ya gonna believe: A guy who lies for a living or your own eyes?

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

Some other stories I found interesting this week. Hope you enjoy.

A Nation Derailed

Like most of you, I haven’t been traveling much lately. But long-time readers probably know that I am a big fan of train travel. My last rail trip was almost a year ago now from Montreal to Halifax on an overnight sleeper train. I loved it.

So, I found this piece by Lewis McCrary a fine primer on why the rest of the world has decent – or in some cases outstanding – rail service, while the U.S. limps along with our sadly underfunded Amtrak system. You can read the story as a metaphor of source for failed American leadership, or at least misplaced American priorities.

“Since its beginnings 40 years ago, Amtrak has insisted that it can become a self-sustaining operation, largely based upon claims like those made in 1971: in high-traffic, high-density corridors like the Northeast, there is sufficient consumer demand that passenger rail can operate at a profit. There has always been some truth to this line of reasoning, but it ignores a question that is at the heart of interstate transportation policy, both for highways and railroads: who pays the enormous costs of building and maintaining infrastructure? Interstate highways were only made possible through large federal subsidies—handouts not unlike those that created the grand railway network in the late 19th century.”

Read the whole piece.

Joan Didion on Bob Woodward

I confess I have never been a great fan of Bob Woodward’s thick tomes on Washington politics. Few can argue with his role – and Carl Bernstein’s – in exposing the crimes of Watergate, but his books have often been the product of absolutely conventional D.C. wisdom, frequently based on his access to key players who, if they play the access game skillfully, usually come off looking OK.

It’s also always bothered me that often Woodward’s books rely almost entirely on unnamed sources. Footnotes matter, after all.

And almost always Woodward becomes, as he has recently, a big part of the story. Yes, I think he erred in not revealing a lot soon what Donald Trump was telling him about the virus.

Still, the latest Woodward is a bit different. He has hours of tapes of Donald Trump. No anonymous source, but the source. Still, with all the hype over Rage, the latest Woodward tome, it strikes me there is less here than meets the eye. It is, as I point out above, no great scoop that Trump is a habitual liar.

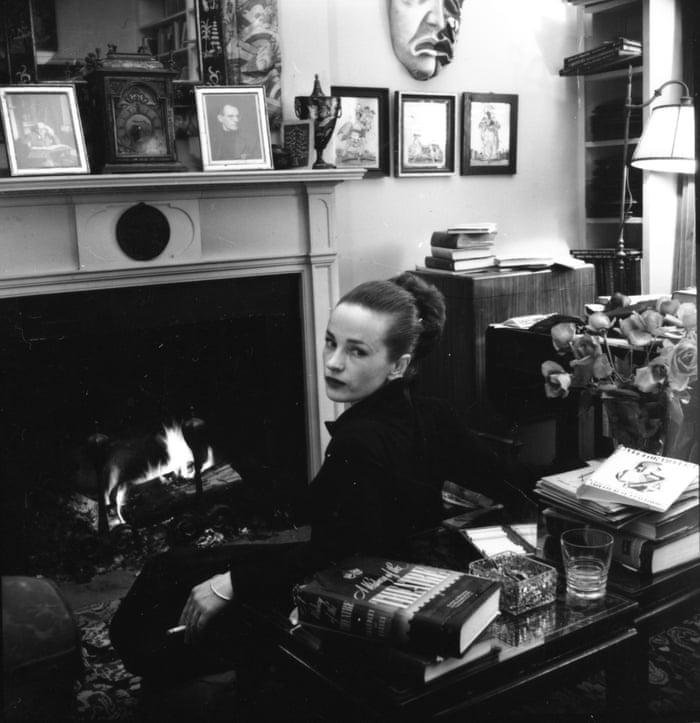

The great Joan Didion was not a Woodward fan either and in 1996 she did a rather epic takedown of the Washington Post reporter/editor. It’s worth revisiting.

“Mr. Woodward’s rather eerie aversion to engaging the ramifications of what people say to him has been generally understood as an admirable quality, at best a mandarin modesty, at worst a kind of executive big-picture focus, the entirely justifiable oversight of someone with a more important game to play . . . What seems most remarkable in this new Woodward book is exactly what seemed remarkable in the previous Woodward books, each of which was presented as the insiders’ inside story and each of which went on to become a number-one bestseller: these are books in which measurable cerebral activity is virtually absent.”

Here’s the link.

After the Gold Rush

In September 1990 – thirty years ago – Vanity Fair magazine published a long piece by Marie Brennan on a New York developer and his then-Czech wife.

The story was an early taste, actually a hearty gulp, of the man who now sits in the White House. Reading it today is a little like having a look three decades ago of what the future would look like in 2020. Brennan wrote:

“I thought about the ten years since I had first met Donald Trump,” Brennan wrote. “It is fashionable now to say that he was a symbol of the crassness of the 1980s, but Trump became more than a vulgarian. Like Michael Milken, Trump appeared to believe that his money gave him a freedom to set the rules. No one stopped him. His exaggerations and baloney were reported, and people laughed. His bankers showered him with money. City officials almost allowed him to set public policy by erecting his wall of concrete on the Hudson River. New York City, like the bankers from the Chase and Manny Hanny, allowed Trump to exist in a universe where all reality had vanished. ‘I met with a couple of reporters,’ Trump told me on the telephone, ‘and they totally saw what I was saying. They completely believed me. And then they went out and wrote vicious things about me, as I am sure you will, too.’ Long ago, Trump had counted me among his enemies in his world of ‘positives’ and ‘negatives.’ I felt that the next dozen people he spoke to would probably be subjected to a catalogue of my transgressions as imagined by Donald Trump.”

Read the whole thing if you have a strong stomach.

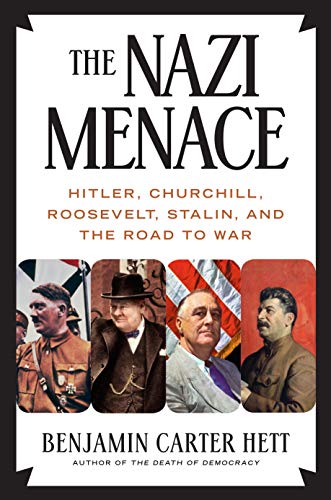

The Nazi Menace

I just finished a fine new book by historian Benjamin Carter Hett, a scholar of modern Germany who teaches at CUNY. It’s called The Nazi Menace and focuses on the event immediately leading up to the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. It’s a fine book and I recommend it to anyone wanting a firmer understanding of these central events in 20th Century history.

Another historian I admire, Fredrik Logevall, reviewed the book for the New York Times.

“For the Western leaders and their populations, the second half of the 1930s represented, Hett argues, a ‘crisis of democracy.’ In the minds of influential observers like Churchill and the American columnist Walter Lippmann, it seemed an open question whether the major democracies could respond effectively to the threat from totalitarian states that were primed for war and had ready access to resources. Could Western leaders mobilize their competing interest groups and fickle constituents to support costly overseas commitments? What if these same constituents fell under the sway of fascism, with its racist and nationalist appeals?”

Read the review here.

Thanks, as always, for following along. Be safe and be well.