The 20 years of American misadventure in Afghanistan, and the deadly, messy departure from that misadventure, is an apt metaphor for our broken, unserious politics.

The congressional hearings this week about the American withdrawal offer a window into the barren soul of not just American foreign policy, but those who pretend to make and influence it. We seemed to have learned almost nothing from two decades of death, destruction, delusion and debt, but assigning blame, as was the purpose of congressional hearings this week, sure makes for a great video clip.

In the period between when a Republican president warned that putting troops and treasure into Afghanistan would mean a long slog to when another Republican president made an ill-considered deal with the Taliban to withdraw, congressional Republicans rarely said a peep about our policy or priorities.

The former chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, James Inhofe of Oklahoma, never once conducted a hearing on the Afghan withdrawal when he chaired the committee. This week he assigned all the blame to a Democratic administration that has been in office for less than a year, because, well, American foreign policy has become all about assigning blame.

Congressional Democrats have an only marginally better record since all but one Democrat who is still in Congress voted to launch the Afghan/Iraq misadventure in the first place.

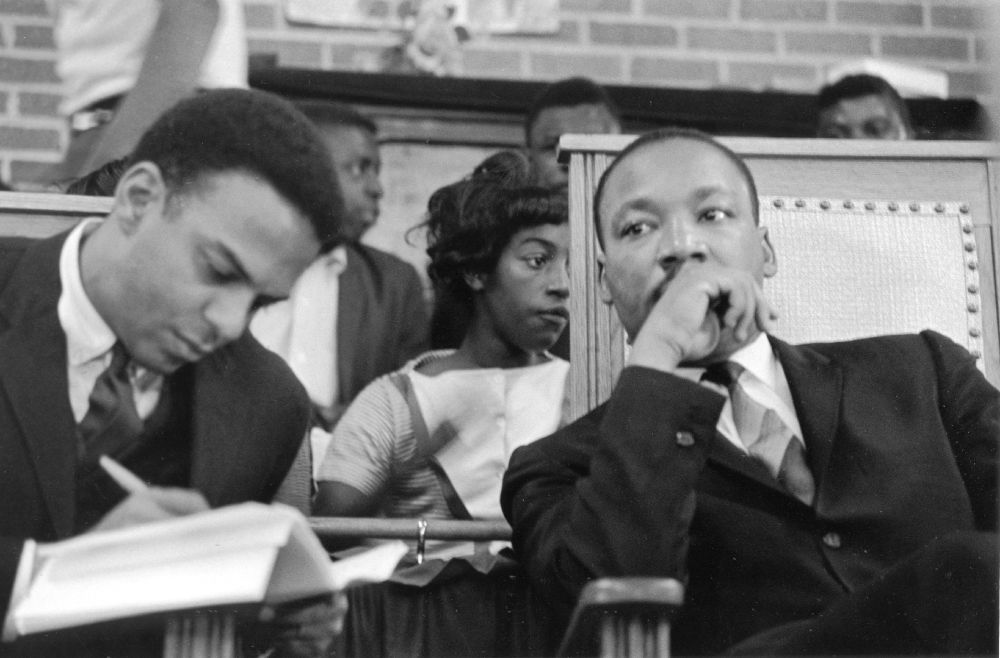

“We must be careful not to embark on an open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target,” California congresswoman Barbara Lee said in 2001 when the House voted to give George W. Bush his blank check for war. “There must be some of us who say: Let’s step back for a moment and think through the implications of our actions today. I do not want to see this spiral out of control.”

The gentlewoman from California had it right. And she knew her history, equating the open-ended authorization to allow every subsequent president to wage war wherever they wanted to Lyndon Johnson’s Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1964 that paved the path to the American misadventure in South Vietnam.

Afghanistan was and is a manifest, bipartisan failure: a failure of congressional acquiescence to presidential power; a failure to recognize America’s catastrophic inability to shape cultures we don’t understand into western style democracies; a failure that imagines the country’s bloated military establishment, propping up a bloated military-industrial complex, can exercise its will at will; and ultimately a failure of American voters to take any of this even remotely seriously.

One of the few bright spots in this week’s performative soundbite trolling on Capitol Hill was the evidence that the current president actually had the backbone to override the advice of his military advisers, who apparently to a man argued to keep American forces in Afghanistan indefinitely.

Republicans, who once won elections on the question of who most supported the military, attacked the chairman of the Joint Chiefs – by one account “assassinated his character and impugned his patriotism” – for his failure to resign when his advice was rejected. General Mark Milley then schooled the odious senator from Arkansas, Tom Cotton, about the critical importance of civilian control of the military. The general might have reminded the senator that American presidents are often at their best when they reject the conventional wisdom of men in uniform, but that may be expecting too much from a military that still cannot imagine its limitations.

Lincoln replaced generals repeatedly, even popular ones. Harry Truman rejected Douglas MacArthur’s advice to bomb China during the Korean War and then sacked the strutting mandarin for insubordination. John Kennedy rejected the advice of his military advisers when they wanted to invade Cuba in 1962. Barack Obama fired another egocentric general for popping off to a journalist. You might argue that civilian deference to gold braid has been out of balance since Vietnam, but to examine that thought you would need a level of discernment and self-awareness impossible for most politicians today.

Afghanistan, with all its mistakes, missteps and misfortunate, cries out for the kind of sober and reasoned debate and review that we seem incapable of mustering.

It is not just Afghanistan, of course, but the failure of our too partisan, too trivial, too odious political class to deal with almost everything. Pick your issue: immigration, infrastructure, income inequality, domestic terrorism, climate, debt, health care – we’re treading water at best, floundering at worst.

And it really is our fault – individually and collectively. We send small people, with small minds and outsized opinions of themselves to do adult work.

“The fault is not in our stars but in ourselves…”

History often celebrates, too late, the naysayers who are prophets, the Barbara Lee’s and the Wayne Morse’s.

Morse, an Oregon senator, was an irascible, pedantic gadfly – a “sanctimonious bore” by one account – and also the kind of politician indispensable in a democracy. Morse early on saw where American involvement in southeast Asia would lead. He was one of two votes in the Senate against LBJ’s Tonkin Gulf resolution, and he also correctly diagnosed where American politics were headed.

“Having abandoned its responsibilities for the big things,” Morse said in 1964, “Congress falls back on making the most of the small things. Frustrated members who fear to question the Pentagon brass, the State Department, and the Central Intelligence Agency, concentrate on the full exercise of more petty powers … having swallowed the camel, Congress strains at the gnats.”

American democracy is imperiled. We know it. Some of us welcome the chaos believing it benefits our tribe. But the fix, if there is one, is not more chaos, not more simple-minded, small-bore politicians focused on today’s soundbite rather than tomorrow’s substance. The fix is to commit to greater seriousness, more personal involvement in a civil and civic life, more engagement with the common good.

Wishing for it isn’t going to work. Electing better people might work, but time is short.

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

Somethings you might find of interest…

The Constitutional Crisis is Here

The historian Robert Kagan authored the most talked about political essay of the season recently, arguing in the Washington Post that a second Donald Trump presidential candidacy is a near certainty, and also a huge threat to American democracy. It is sobering stuff.

“The world will look very different in 14 months if, as seems likely, the Republican zombie party wins control of the House. At that point, with the political winds clearly blowing in his favor, Trump is all but certain to announce his candidacy, and social media constraints on his speech are likely to be lifted, since Facebook and Twitter would have a hard time justifying censoring his campaign. With his megaphone back, Trump would once again dominate news coverage, as outlets prove unable to resist covering him around the clock if only for financial reasons.

“But this time, Trump would have advantages that he lacked in 2016 and 2020, including more loyal officials in state and local governments; the Republicans in Congress; and the backing of GOP donors, think tanks and journals of opinion. And he will have the Trump movement, including many who are armed and ready to be activated, again. Who is going to stop him then? On its current trajectory, the 2024 Republican Party will make the 2020 Republican Party seem positively defiant.”

I’ve taken to thinking of myself as (I hope) informed, but a pessimist. This piece made me really nervous.

Why I’m A Single Issue Voter

I’ve long considered Mona Charen among the most orthodox of conservatives – a columnist of the Reagan/Bush ilk. In a recent piece she argued that she’s voting for the Democratic candidate for governor in Virginia next month, because the only issue that matters right now is, well, truth.

“The Republican party, in Washington and nationally, has become a conspiracy of liars. As such, it threatens the stability of the republic. Even a seemingly inoffensive candidate like Glenn Youngkin has given aid and comfort to this sinister agenda by stressing ‘election integrity’ in his campaign. It doesn’t change a thing to reflect that he’s almost certainly insincere. He stopped talking about it after winning the primary, suggesting that all the “integrity” talk was just a sop to MAGA voters. Still, a victory for him will send a message that the Republican party is normal again, a party that good people can support.”

Charen’s tour of the current GOP is also pretty chilling.

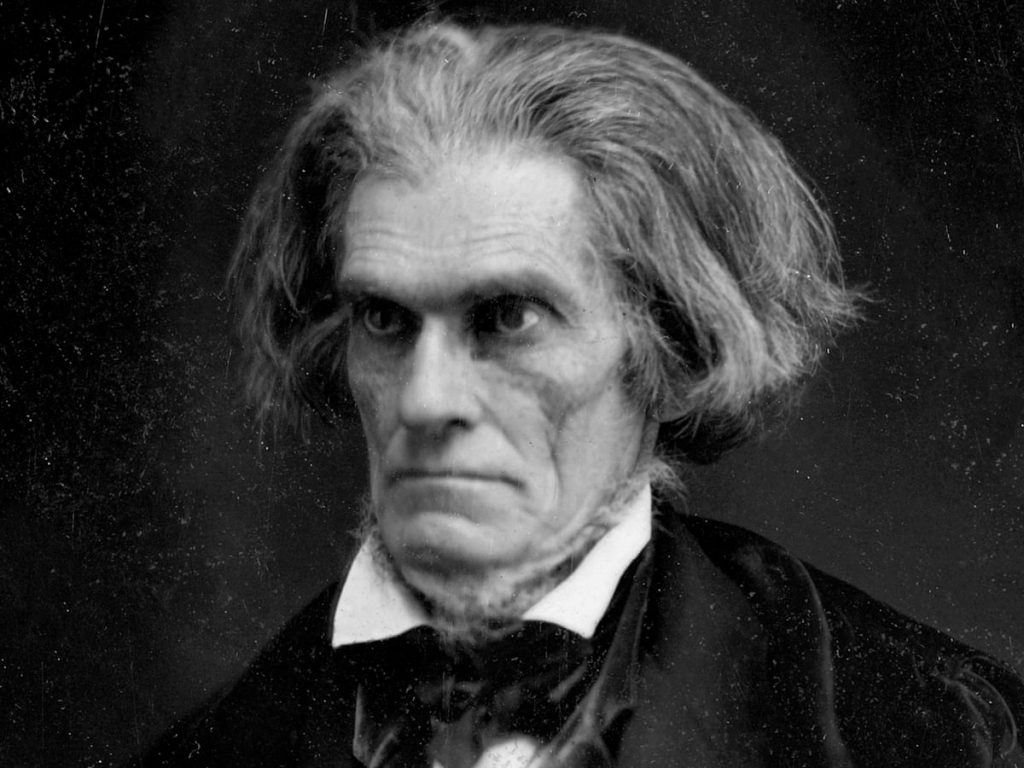

Pro-slavery Senator John C. Calhoun Opposed Infrastructure Spending for a Reason.

A really interesting piece here from a historian of the Civil War era on slavery and infrastructure. Seriously.

“Calhoun is rarely thought of as a monetary theorist, but his comments on monetary architecture and government spending are surprisingly relevant. Though nearly two centuries old, they hold a lesson about the politics of austerity today, as Republicans oppose needed federal investment in green technology and infrastructure, climate change mitigation, pandemic preparedness, affordable housing, equitable broadband access, and low-cost, high-quality education from pre-K to college. To realize these goals, which are both popular and urgently necessary, federal, state, and local governments will have to deploy the full scope of their fiscal and monetary capacities. We who support those goals can expect Republicans (and corporate Democrats) to blow a lot of smoke in our eyes, generating word cloud after word cloud dominated by ‘deficits,’ ‘inflation,’ and ‘pay-fors.’ Calhoun can help clear the air. His ideas expose the conservative, hierarchical commitments that have always worked to thwart the promise of democratic governance.”

Daniel Craig Will Now Take Your Questions

Sean Connery is still my ideal James Bond, but you have to admit Daniel Craig has filled the role of the Brit spy like few others. Something a bit lighter here, and pretty funny.

“At 53, Craig is cheerful and clever and friendly. He has bright blue eyes in a tanned and tired face. It is day five of six at the junket which may or may not decide the future of cinema, and he is about 36 hours off quitting Bond for ever. After 2015’s Spectre (most of which he filmed with a broken leg), Craig notoriously claimed he would rather slit his wrists than return to the role.”

From The Guardian, and some of the questions are great.

An old journalist friend of mine is fond of saying that “the press can dish it out, but we don’t have to take it.” I thought of that great one liner as what might have been – should have been – a serious discussion of federal budget policy over the last week turned into a junior high school style story about Bob Woodward, the ultimate Washington insider, being “threatened” by a mild-mannered White House economic adviser.

An old journalist friend of mine is fond of saying that “the press can dish it out, but we don’t have to take it.” I thought of that great one liner as what might have been – should have been – a serious discussion of federal budget policy over the last week turned into a junior high school style story about Bob Woodward, the ultimate Washington insider, being “threatened” by a mild-mannered White House economic adviser.