This piece first appeared in the Lewiston, Idaho Tribune

———–

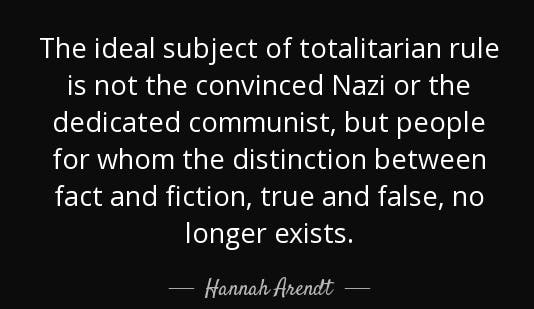

Historians, philosophers and ethicists have been debating for nearly 60 years – perhaps longer really – the notion that a person can do evil without being evil. That question is at the heart of philosopher Hannah Arendt’s description of Adolph Eichmann, the Nazi bureaucrat who implemented Hitler’s slaughter of six million Jews during World War II.

Eichmann was abducted from his Argentine hiding place in 1960, taken to Jerusalem, tried for war crimes and executed in 1962. Arendt covered Eichmann’s trial for The New Yorker and found the defendant to be a rather ordinary, unassuming little man. Thomas White wrote about what Arendt called “the banality of evil,” and says she found Eichmann “neither perverted nor sadistic”, but “terrifyingly normal” acting “without any motive other than to diligently advance his career in the Nazi bureaucracy.”

It is an interesting – and still controversial – notion: that “normal people” are capable of abnormal, even horrible things in service to their own ambition, or perhaps due to their inability to assess the moral dimensions of their actions.

Watching the recent viral video of a U.S. Justice Department attorney appearing before a panel of three federal judges and being unwilling to say that migrant children in government custody being denied basic sanitation, soap and a toothbrush, or a decent place to sleep was unacceptable left me thinking again about Hannah Arendt’s theory.

And before you think that I’m equating a government lawyer with a bureaucrat of the Holocaust, I’m not. The question is rather about the human capacity, even the need, to look the other way, to disengage, to accept the unacceptable, to reduce what we all know to be wicked, wrong or malicious to, well, the banal, the commonplace.

A bumper sticker was in wide circulation some years ago: “If you’re not outraged you’re not paying attention.” It should make a comeback.

The fault is in all of us. We too easily become numb to an outrage, a scandal, a violation of norms and traditions, particularly if it all fits comfortably with an otherwise settled and pleasant personal opinion.

Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential candidate and senator from California, for example, recently said if she happens to become president she wants to see that the Justice Department goes “forward with those obstruction of justice charges” against Donald Trump. Harris was roundly criticized, as she should have been, for saying, as the Brookings Institution’s Benjamin Wittes wrote, “that as president you would supervise that person’s prosecution, as Harris did, is poisonous stuff in a democracy that cares about apolitical law enforcement.”

Trump, of course, has done the same thing by encouraging “lock her up” chants at his rallies and suggesting that his political opponents should be investigated or in jail. That Trump would engage in such poisonous stuff is wrong and that a Democrat would mimic the poison is just as wrong. You cannot accept one and condemn the other unless you have become numb to outrage.

When the president of the United States was once again credibly accused – actually for the 22nd time – of sexual assault, a crime he actually admitted to in the infamous Access Hollywood tape, there was a collective yawn. Many major news organizations barely covered the story, even when Trump dismissed the allegation bizarrely saying: “I’ll say it with great respect: Number one, she’s not my type. Number two, it never happened. It never happened, OK?”

One of the great normalizers of the abnormal in our times, South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, simply said: “He’s denied it and that’s all I needed to hear.” Graham, of course, had a much different reaction to Trump’s comments in that infamous videotape in 2016: “Name one sports team, university, publicly-held company, etc. that would accept a person like this as their standard bearer,” he said. That was then. This is now.

“When you know you can lie constantly and effectively not be held accountable,” the commentator John Ziegler wrote recently, “it is like an offensive line in football free to break any rule they want, secure that even if they get called for holding, the penalty will not be enforced.”

We believe what we want to believe and we discount the lies we find at odds with what we want to believe. We casually dismiss a troubling outrage if confronting it requires a reckoning with our own values. In such a situational world the inconvenient is just a temporary nuisance. How else to explain a government official justifying keeping kids in abhorrent conditions as if the government had no power to change those conditions?

Or a Saudi journalist working for an American newspaper is brutally murdered with credible evidence the Saudi crown prince was involved, but those inconvenient facts aren’t allowed to stand in the way of selling billions in military equipment to a profoundly corrupt Saudi government. An Idaho politician is in a key position to make a stink. His silence is deafening.

The chief executive repeatedly demeans the head of the Federal Reserve, undermining more than 100 years of tradition that the country’s central bank is insolated from political interference. An Idahoan chairs the key Senate committee that plays a critical role in ensuring that independence. He has never said a word, let alone used his influence to affect such behavior.

A top Democratic appointee in Idaho state government, a state tax commissioner, mysteriously is placed on “administrative leave” and just as mysteriously returns. No explanation is offered. No accountability is demanded. Democrats are silent. Republicans are mute.

Offer a hundred other examples of the normalization of outrage from the perspective of your own worldview, but also ask why is any of this acceptable? Why has such behavior on so many levels in so many ways become banal?

The fault, as the bard so eloquently wrote, is not in our stars, but in ourselves. If you’re not outraged, you really are not paying attention.