What if the American experiment has reached its sell by date?

What are the chances the 244-year run of “the last best hope on earth,” as Lincoln said, is not just in twilight, but already too far gone to save?

Lincoln’s hope for the world depended on, he said, “plain, peaceful, generous, just” actions by Americans who profoundly disagreed about big issues but were still bound together by a common purpose – to be part of a country bigger and better than its differences.

What if the United States of the 21st Century is not the place Lincoln thought it to be, but just too big, too diverse, too divided, its population too invested in tribal loyalties and hatred, too eager to condemn, too sure of its own righteousness and too certain of its disdain to survive? What if our 244 years of failing to really confront the original American sin of permitting, indeed encouraging, human bondage has finally visited a reckoning on us?

What if the parallel crisis of race, pandemic, economic and climate upheaval is just too much for our inadequate leadership, our fractured social compact and our wildly differing views of reality to handle?

What if surviving world wars, economic collapse, including a decade-long depression, a deadly pandemic a hundred years ago and the catastrophe of civil war in the 1860s was just part of a trial run for ultimate failure in the 21st Century? What if “the last best hope” isn’t?

I confess that I have never before, even in the abstract, really considered that the end might come. The United States is, after all, as we used to tell ourselves, “the indispensable nation.” The “greatest country” on the planet. We had the biggest economy, the best health care, the most freedom. We are, or we told ourselves we were, “exceptional.”

But now we see it was all a lie. We told ourselves stories about how great things are and we believed our own press releases. We said the American system – checks and balances, fair and free elections, holding people accountable, the “rule of law” – could be shaken from time-to-time, but would endure. The idea, we told ourselves, was that our very special Constitution would protect us from crooks and charlatans and despots. Congress would exercise its independence and hold a chief executive who got too big for the Constitution accountable. After all, Republicans told Republican Richard Nixon that the jig was up, and he had to go. The system worked. Back then.

Not to worry, we convinced ourselves, American ideals, perhaps never fully realized, like the “all men are created equal” language not really applying to all persons, would still, by hook or crook, prevail.

We got this covered we assured ourselves. A momentary blip in the body politic and before you know it, we’ll be back on the path to perfecting “a more perfect union.” But we aren’t on that path. Our current path is down a long, dark alley were division and discord seem to be the only truly exceptional things about the country.

As Thomas Geoghegan recently put it perfectly: “we are at a moment like the one the country faced in 1932 – there is not just fear and uncertainty and a sense of being unmoored but also the doubt that our form of government is capable of coping. In a way it is even worse: unlike in 1932, the plot against America is already in full swing, and we as a people are even more uncertain of who we are.”

A thing to remember about the United States is that it’s just an idea, and an idea built on a very flimsy foundation. It’s not the laws and the Constitution that ultimately matter, but rather that people – citizens and their leaders – will decide, even when it means acting against immediate self-interest, that they will still act in good faith. The idea is that respect for the norms of a democratic society will be observed and that decency will ultimately prevail, even if observing the norms and behaving decently mean that my side is going to lose some of the time. How obsolete that seems today.

If America is not to pass away into something Lincoln would not recognize, that Franklin Roosevelt would find repugnant, that General and President Eisenhower would reject, we need to recapture a shared sense of national purpose.

We can begin with a fundamental question. What do we really stand for? It’s not that we stand for any one president or any one political position, but what is really in the American DNA?

The Catholic scholar Thomas Levergood takes me back to my own belief in my church’s social message, which is to search for and find “the common good.” Levergood recently defined the idea in an essay in the Jesuit journal America: “In a specific sense a common good refers to something that can only be shared in common and cannot be divided in pieces and be possessed by individuals or smaller groups. It is a common end achieved through common actions.”

Levergood continues: “It is in plain view that many of our fellow citizens are so frustrated with our political system that they have fallen for populist rhetoric to condemn all ‘politicians’ or government itself as evil. (Others are taking out their frustrations by tearing down statues.) This situation derives not from bad ideas or faults in the American people but rather from lacking the common good of a functioning political system.”

We fix what ails America and avoid obsolescence by rededicating ourselves as citizens to creating a functioning political system that aims squarely at the common good, not what’s good for a Republican or a Democrat, a socialist or a libertarian, a conservative or a liberal, but an American.

Deirdre Schifeling, who heads an organization dedicated to expanding voting rights, recently told The Guardian she believes this election marks a tipping point in America, a moment in which the country, having been jolted out of its complacency, will rebound. “Faith in our democracy is at an all-time low and that is very dangerous. Now the work begins on fixing it.”

Let’s hope she’s right. And let’s find our common purpose before it’s too late.

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

A collection of pieces I found of interest this week and I hope you will, too.

130 degrees

The climate crisis came home to us in western Oregon this week. The worst and most deadly fires in recorded memory destroyed homes and businesses and brought death – not to mention vast layers of smoke – to often wet and green Oregon.

If you any longer think that climate change is a hoax, I have some air for you to breath on the north coast. And then read this piece by Bill McKibben in the New York Review of Books. Absolutely frightening.

“Depending on the study, the risk of ‘very large fires’ in the western US rises between 100 and 600 percent; the risk of flooding in India rises twenty-fold. Right now the risk that the biggest grain-growing regions will have simultaneous crop failures due to drought is ‘virtually zero,’ but at four degrees ‘this probability rises to 86%.’ Vast ‘marine heatwaves’ will scour the oceans: “One study projects that in a four-degree world sea temperatures will be above the thermal tolerance threshold of 100% of species in many tropical marine ecoregions.” The extinctions on land and sea will certainly be the worst since the end of the Cretaceous, 65 million years ago, when an asteroid helped bring the age of the dinosaurs to an end.

Quite a legacy to live to the kids and grandkids. Read it all here.

The Truth is Paywalled, the Lies are Free

Nathan J. Robinson, writing in Current Affairs, has a really good and provocative piece on access to information. He notes that quality sources of information – the New York Times, Washington Post, New York Review, Times of London, Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, among others – have their content (for the most part) behind a “paywall,” while “Breitbart, Fox News, the Daily Wire, the Federalist, the Washington Examiner, InfoWars” are free!

You do get what you pay for (this site not withstanding).

Robinson is really arguing for a system of uniform, free access to all kinds of content that doesn’t screw over the producers of the content. Worth your time.

Joey Biden, He Could Really Talk

The late Richard Ben Cramer wrote what political junkies (like me) consider the best presidential campaign book – ever – called What it Takes.

It might just be the best political book ever. Cramer focused on the candidates who ran for president in 1988, including a guy named Joe Biden.

Trust me, it’s worth your time.

“Joe did not stutter all the time. At home, he almost never stuttered. With his friends, seldom. But when he moved to Delaware, there were no friends. There were new kids, a new school, and new nuns to make him stand up and read in class: that’s when it always hit—always always always. When he stood up in front of everybody else, and he wanted, so much, to be right, to be smooth, to be smart, to be normal, j-j-ju-ju-ju-ju-jus’th-th-th-th-then!

“Of course, they laughed. Why wouldn’t they laugh? He was new, he was small, he was … ridiculous … even to him. There was nothing wrong. That’s what the doctors said.

“So why couldn’t he talk right?” Read the excerpt here.

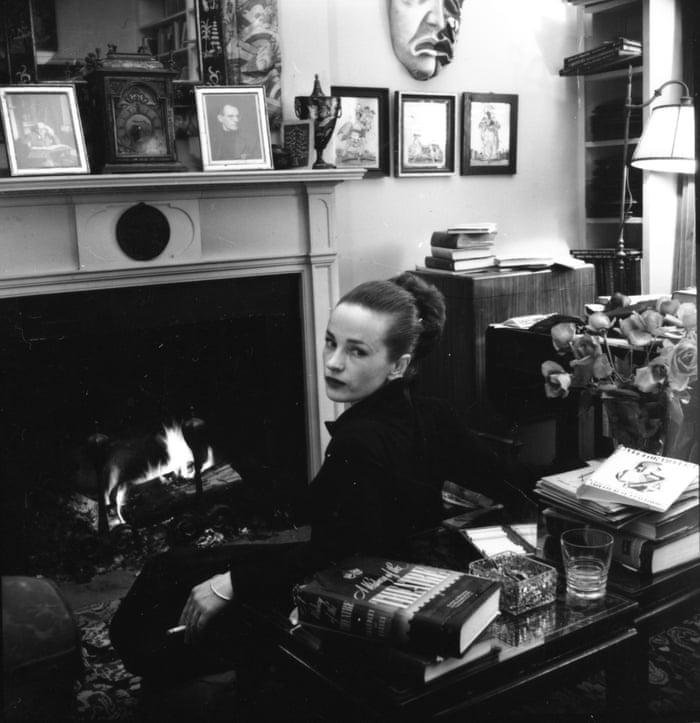

She laid waste to a “dozen-odd writers and artists

I really loved this piece in the London Review of Books, a book review really of works by and about Maeve Brennan, a long-time writer for The New Yorker. It was said Brennan “could stop traffic” and was the inspiration for Truman Capote’s character Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

“At the New Yorker, with her ‘longshoreman’s mouth’ and ‘tongue that could clip a hedge’, she made her opinions known. Daphne du Maurier was ‘witless’, Jean Stafford her ‘bête noire’. Brennan immediately set her sights on grander things than the fashion notes and short reviews she’d been hired to write. In 1952, her first story appeared; two years later, she had a piece in ‘The Talk of the Town’, the section of the magazine over which [William] Shawn kept the tightest of reins. Brennan’s male colleagues, including [the cartoonist Charles] Addams, Joseph Mitchell and Brendan Gill (all of them her lovers at one time or another), joked that she had served her apprenticeship in hemlines. But it was the ability to spot the difference between ‘beige’ and ‘bone’ at fifty yards that made her a natural diarist. John Updike said her ‘Talk of the Town’ pieces ‘helped put New York back into the New Yorker’.”

Thanks for reading. If you know someone who might be interested in these weekly posting please let me know or have them sign up at the website.

Stay safe. Be well.