Courts are not leaders in social change. They follow after movement in the larger society. That was true with respect to racial justice. It’s true, now, with the women’s movement. It’s true with the LGBTQ movement. How long that discrimination lingered when people were hiding in closets. Change occurred only when they came out and said, “This is who we are, and we’re proud of it.” Once they did that, changes occurred rapidly.

——

Before the politics takes over completely – it might already be too late – let’s reflect on the person of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her remarkable story of courage and perseverance.

“Born the year Eleanor Roosevelt became First Lady,” historian Jill Lepore wrote in The New Yorker, “Ginsburg bore witness to, argued for, and helped to constitutionalize the most hard-fought and least-appreciated revolution in modern American history: the emancipation of women. Aside from Thurgood Marshall, no single American has so wholly advanced the cause of equality under the law.”

And as the Washington Post editorialized: “The America we inhabit today, where women fly military fighter jets, occupy a quarter of the U.S. Senate and account for half of all first-year law students, is a different and better — though still far from completely equal — nation, due in no small part to the courageous career of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.”

There is much to be said – and celebrated – in the life of the second woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Better tributes than I can possibly offer had been made since her death on Friday. I recommend this, and this and this.

The tenor of our times, sadly, means the celebration and mourning of the legendary RBG gave way almost immediately to the rank political rush to determine who might replace her. It is an unsightly, indeed gross example of how far into crisis our democracy has fallen.

It shouldn’t be this way, it doesn’t have to be this way. Make no mistake if the effort to fill a Supreme Court seat moves ahead as it now looks likely it will – weeks before a bitter and contentious presidential election where the majority in the Senate also stands in the balance – the outcome will almost certainly spell disaster for the Court, the Senate and the country.

It is a moment when democracy and fairness and the future demand something that seems wholly absent from our politics – restraint.

——-

Given the current state of our politics, it is surprising – really surprising – to recall that Ruth Bader Ginsberg was confirmed as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1993 by the astounding Senate vote of 96-3.

You read that right, three very conservative Republican senators – Helms of North Carolina, Nickles of Oklahoma and Smith of New Hampshire – voted “no” on her confirmation. The rest of the Senate said, yes.

Hard core conservatives like Orrin Hatch of Utah, Larry Craig of Idaho and even Strom Thurmond of South Carolina found the diminutive judge worthy of breathing the rarified air of the Supreme Court.

Ginsberg’s confirmation when it finally happened was a big story, but not a huge story. The New York Times featured a photo of RBG on its front page – August 4, 1993 – but the full story was relegated to page eight in the “B” section of the paper. Not exactly high profile.

The Times cover that day was given over to Bill Clinton’s struggle to pass his budget and tax plan and the looming genocide in Bosnia. The confirmation of arguably one of the most significant Supreme Court justices in America history was, well, kind of an afterthought. No one really believed that Ginsburg – scholar, advocate, respected judge – was not fully qualified by experience, character and temperament to serve. Her subsequent years on the Court proved the wisdom of that judgment.

But now the political discussion is about whether the Court will have a 6-3 conservative majority, whether an anti-abortion, anti-Affordable Health Care Act majority can be created, whether the Court will be favorable to conservatives for a generation or more. Needless to say, this does not seem like the way a democratic system selects judges who will enjoy widespread public confidence.

Dave Leonhardt in the New York Times has an excellent rundown of Supreme Court politics since 1968 when Lyndon Johnson’s pick to replace retiring Chief Justice Earl Warren was rejected by the Senate on grounds that Justice Abe Fortas’s ethical behavior disqualified him. Richard Nixon, instead, made the appointment after the election of Warren Burger and the Court began a long-term turn to the right.

I won’t recount all the history here but will note that both parties have played this ideological game from at least 1968. In retrospect the bruising fights that kept Robert Bork off the Court and put Clarence Thomas on deeply shook the Senate. Each subsequent fight has its roots in the previous nasty confrontation.

As a result, the confirmation spotlight has shifted over time from questions of basic competency and experience to pure ideology. That Thomas and the newest justice, Brett Kavanaugh, were credibly accused of sexual misconduct further inflamed the process, with Republicans placing the conservative qualifications of a Court candidate over any possible question of character.

So, both parties share the guilt for where we are, but there is little doubt that Republicans have played the Court games more astutely, more ruthlessly and with what now appears will be one of the most blatant examples of political hypocrisy in modern times.

All the efforts to parse and footnote the Republican position from 2016 when Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell refused for eight months to consider President Barack Obama’s nomination of federal Appeals Court Judge Merrick Garland can be reduced to one word – hypocrisy. Of it you prefer two words – shameless hypocrisy.

(Writing in The Bulwark, Jonathan V. Last, a conservative, offered another perhaps even more fitting description of GOP strategy. Republicans are, Last wrote, “deploying situational ethics in a nihilistic pursuit of power.”)

Yet, beyond the raw exercise of political power there are things even more important at stake.

——

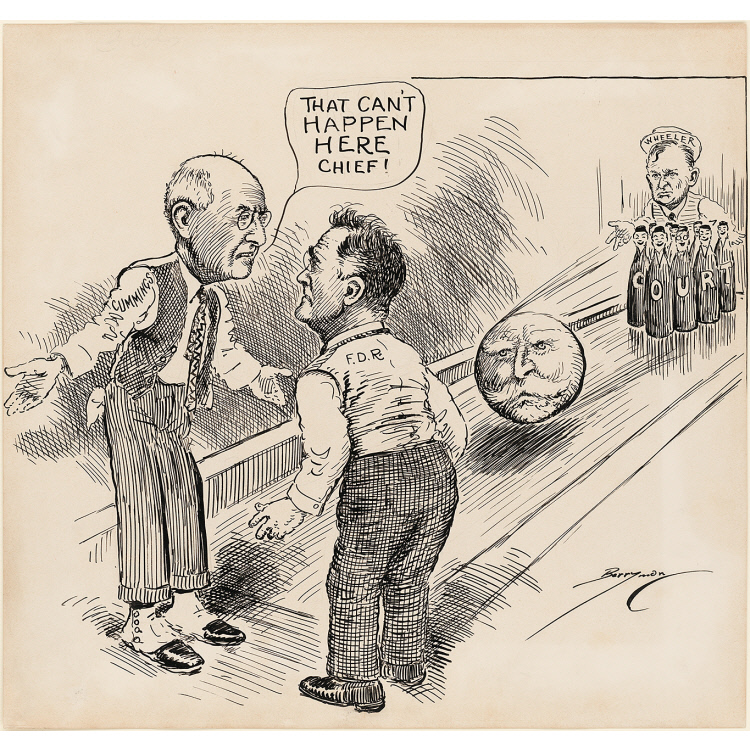

The most famous Court fight in American history took place 83 years ago this summer. Franklin Roosevelt, at the absolute zenith of his political power after a landslide re-election in 1936, decided to “pack” the Court. FDR wanted to install six new judges. The Court would have grown from nine members to 15 in one crushing example of presidential power. Roosevelt fully expected that fellow Democrats who dominated the Congress – 76 Democrats sat in the Senate – would happily go along. Many Democrats, after all, owed their political careers to the powerful man in the White House and Roosevelt seemed to command public approval for virtually whatever he wanted to do.

But rather than bend to the president’s will, a move that would have drastically remade the Court and fundamentally called into question its independence, indeed legitimacy, Democrats rebelled.

The leader of the Senate opposition to Roosevelt’s power grab was a tough, independent progressive Democrat from Montana.

I wrote a chapter on this fight in my 2019 biography of Senator Burton K. Wheeler. Wheeler, like all politicians, had complicated motives for opposing the extremely popular president of his own party. He disliked Roosevelt personally and politically. Wheeler harbored presidential ambitions. He was given to waging high profile battles, even if the odds seemed long. The guy had courage and conviction.

Still, the verdict of history gives Wheeler not only a win for stopping Roosevelt’s court packing, but also, I believe, for saving the Supreme Court. He correctly saw that by not tempering his ambitions and by exercising the political power that he clearly possessed, Roosevelt would in effect make the Court subservient to the executive. Balance of power would have been dinted or likely destroyed.

Wheeler understood that the Court as an institution was more important than any political moment, that the integrity of the Court and the Senate were fundamental to a functioning democracy.

Roosevelt was furious. He took out his displeasure on those who opposed him, including Wheeler. But by exercising the restraint that Roosevelt ignored, I would argue, American democracy was actually strengthened. The integrity of the Court was preserved. The Senate’s ability to restrain a powerful president was strengthened. The system worked.

Contrast that with Donald Trump’s comments on Monday: “When you have the Senate, when you have the votes, you can sort of do what you want as long as you have it.”

Conservative judicial scholar Adam J. White, who has heartily supported Trump’s judicial picks up to this point, puts a fine point on the moment: “Indeed, when the constitutional crisis of our time is a crisis of the failure of self-restraint, that crisis will only end when one side restrains itself at the very moment when it cannot be restrained by the other side. For Republicans, that moment is right now, and the fact that self-restraint would be so painful is itself the best evidence that self-restraint is so necessary.”

The Supreme Court has long been politicized. Judges are, after all, the products of the political process. Neither side in our politics sees the Court in anything other than starkly political terms. The atmosphere is beyond toxic, which is precisely why those in power – with the absolute “right” to act – need to step back.

We face the political equivalent of the nuclear deterrent strategy of “mutually assured destruction.” A Republican effort to replace Ruth Bader Ginsberg in this way at this time will almost certainly prompt an equal or greater response. Democrats are already calling for “packing the Court,” adding hundreds of new ideologically chosen judges and mandating judicial term limits, among other things.

What needs to happen – and I’m in no way optimistic it will – is a step back from the certainty that already stressed democratic institutions will be horribly damaged if this unfolds the way it appears it will.

The word is restraint. A fundamental principle of democracy is that people in power must act in ways that preserve and protect the integrity of the institutions entrusted to their care. Having the power to act sometimes demands not acting.

In our lifetime there has never been a better moment to pause, consider and practice restraint.

—–0—-