Nearly 100 years ago — April 15, 1922 to be exact — a Democratic senator from Wyoming introduced a resolution in Congress that touched off one of the most significant investigations in American political history. The Wall Street Journal had reported the day before that the secretary of the Interior, a former Republican senator from New Mexico by the name of Albert Fall, an appointee of President Warren Harding, had engaged in unprecedented conduct. Fall had leased to a private company, without competitive bids, U.S. naval oil reserves at a remote field in Wyoming known as Teapot Dome.

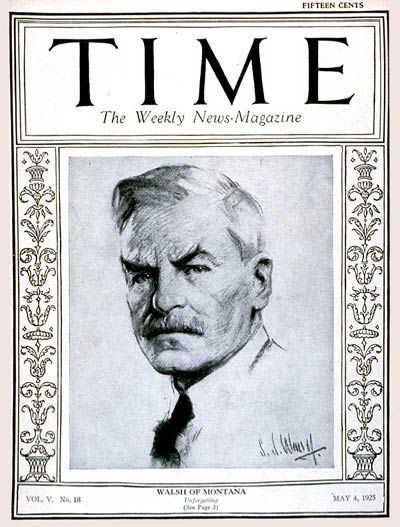

Republicans, who controlled the Senate, actually voted to investigate the Republican administration. But expecting the investigation would come to nothing, they detailed the most junior member of the Public Lands Committee, Montana Democrat Thomas J. Walsh, to chair the investigation.

By the time Walsh was finished cataloguing Fall’s corruption and the bribes he received for facilitating the oil leases, the secretary was on his way to jail. Walsh became a political celebrity and Teapot Dome entered history as one of the great scandals in American politics.

An offshoot of the oil scandal was a parallel effort to investigate corruption at the Justice Department, an investigation also conducted by a Montanan, Democrat Burton K. Wheeler.

When the subjects of that investigation stonewalled the Senate, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Congress had the power to issue subpoenas, compel testimony and demand production of documents. As the court noted in a landmark 1927 decision, the memory of James Madison was invoked, “the power of inquiry — with process to enforce it — is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function. It was so regarded and employed in American legislatures before the Constitution was framed and ratified.”

Said another way: Congress’ oversight and investigative functions were legitimately earned amid a huge scandal uncovered by a newspaper and investigated by determined lawmakers. Now, decades later, congressional oversight and accountability is being frittered away amid a host of real and potential scandals by an administration that seems destined to replace Harding’s as the most corrupt in history.

The Trump administration has apparently determined that it will comprehensively stonewall oversight by a co-equal branch of government. The president says the executive branch will resist every subpoena for information, while the attorney general of the United States flips his middle finger to the House Judiciary Committee.

And the United States Senate — where Teapot Dome was exposed, where a corrupt attorney general (Harding pal Harry Daugherty) was forced to resign, where Harry Truman investigated the defense industry and where the crimes of Watergate were disclosed — continues to squander its constitutional obligations to investigate and check the executive branch.

As the Salt Lake Tribune noted in a recent editorial, “By abandoning the role the Constitution assigns them, to jealously defend the power of their branch of government against encroachments by other branches, Republicans in Congress surrender their duty, their power and their part in defending American democracy.”

Idaho’s two U.S. senators are poster boys for this shameful dereliction of duty.

Jim Risch has had the gavel of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee now for nearly five months, months when the NATO alliance has been under siege from the White House, when Venezuela has been in crisis, when North Korea has saber-rattled with new missile tests, when tensions have mounted with China and Iran, and when Saudi Arabia has escaped responsibility for the brutal murder of a journalist employed by a U.S. newspaper. Yet Risch has required no testimony on any of this from the secretary of state or other senior administration officials.

Each of Risch’s public statements toes the administration line even as that line shifts and wobbles with incoherence.

Risch is also a senior member of the Intelligence Committee but has no interest in questioning the attorney general or special counsel Robert Mueller on the extensively documented Russian effort to interfere with American democracy.

Mike Crapo is a member of the Judiciary Committee, the committee that recently endured a word salad of obfuscation from Attorney General William Barr on the Mueller report. Crapo, rather than focusing on the substance of the special counsel’s work, used his precious time to question the nation’s top law enforcement official about how the Washington Post obtained a copy of Mueller’s letter taking issue with how his work has been characterized by Barr.

Crapo might have asked, just as one example, about this sentence from Mueller’s report: “Our investigation found multiple acts by the President that were capable of exerting undue influence over law enforcement investigations.” Crapo didn’t display even a hint of inquisitiveness about the Russian investigation or the president’s behavior, but spent the hearing serving up softballs. His and Risch’s performance is rank political incompetence or, perhaps, it’s something else even more troubling.

Senate Republicans could well be ignoring their constitutional obligations, as the Salt Lake Tribune suggested, “To get themselves on the good side of a chief executive who is so clearly corrupt, engaging in obstruction, campaign and ethics violations, using the presidency as a cash cow for his personal business interests, who disrespects the separation of powers, freedom of the press, the rights of minorities and immigrants and our long-standing international alliances.”

In other words: Crapo, Risch and fellow Senate Republicans have willfully surrendered their own and congressional power for wholly partisan political reasons.

By consistently placing loyalty to a president of their own party above the institution of the Senate and the good of the nation, they mock a sworn oath to “support and defend the Constitution” against all enemies.

Political courage is an increasingly rare commodity these days and playing to the prejudices of your partisan tribe trumps all other considerations. But that is not what the job — or the oath — requires.

While it may seem quaint to invoke the Constitution as a guide to appropriate congressional behavior, it has never been more important to do so. Democracy may well die in darkness, but it also dies when people sworn to protect it ignore their responsibilities and that is what Risch and Crapo are doing.

—–0—–