In one of the many scenes of dark comedy in the 2017 film The Death of Stalin, the Soviet Union’s dictator is lying on the floor of his Kremlin dining room, obviously near death from a massive stroke. But the cringing sycophantic figures who discover their bosses’ lifeless body – Stalin’s henchmen and would be successors – are paralyzed with fear.

Do they call doctors and if so which doctors? Do they try to save Stalin or let nature take its course? One of them will surely emerge as the new leader, but how best to position for that opportunity?

“He’s feeling unwell, clearly,” says the actor playing Lavrenti Beria, the ruthless Soviet-era security chief who carried out Stalin’s purges until he, like so many others, faced his own show trial and death. Beria graced the cover of Time magazine in July 1953, by Christmas he had been executed.

“The problem, for all concerned, is the idea of a Stalin-free land,” film critic Anthony Lane wrote in a review of the film. “If they must jockey for his throne, which of them will be bold enough to start the fight, with their lord and master still breathing? What will happen if, by some miracle, he rallies and learns that certain underlings presumed to step into his unfillable shoes? Meanwhile, he needs the finest professional care, but regrettably most of the doctors in Moscow have been purged at Stalin’s command.”

The film, which was banned in Russia and several of the old Soviet states, is not a documentary, and some critics have pointed to its mistakes of history, but it is an effort to use a bleak comedy to showcase the perverse and ironic nature of the cult of personality that came to surround Josef Stalin. The fact that the most obvious truth – Stalin was very ill and might well die, which he eventually did – became unspeakable even for the powerful men who worked beside him inside the Kremlin.

As the British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore wrote in his acclaimed biography of Stalin, at the time of his stroke and eventual death in 1953 the men closest to Stalin were obsessed with their own power and “the decision to do nothing suited everyone.” They waited for hours to summon doctors because, as Montefiore notes, “Stalin’s own doctor was being tortured merely for saying he should rest.” The slimy, vile characters around the dictator were “so accustomed to [Stalin’s] minute control that they could barely function on their own.”

While Stalin lay gravely ill the Associated Press reported that the official medical communique from the Kremlin – Stalin was ill but getting the best possible care – was broadcast over and over, amid rumors that he was on the verge of “a remarkable recovery.”

Another widely reported story noted how thoroughly the Russian people had been flooded with the image of the 5-foot 5-inch Stalin as a man of destiny, the “Great Genius Stalin.” During a radio broadcast, a Soviet commentator – presumably with a straight face – said, “There is not and never has been any other man in the world of so varied, so rich, so ubiquitous a genius…his forecasts make no mistakes. His instructions lead to the desired goal. His plans always come true.”

The buildup of Stalin “has been so great the average Soviet worker and peasant might well ask who could possibly take his place.” That was the point.

Truth was dead in the old Soviet Union long before Stalin was. The people around him couldn’t trust each other with the truth. The cult of personality, and the fear that perpetuated it, demanded adherence to the most fanciful lies and made a virtue of the most outrageous claims. It all eventually tumbled down amid vast death and destruction.

One of Stalin’s most loyal lieutenants, Nikita Khrushchev, ultimately outed Stalin only three years after his death. The great man was a fraud, a murderous thug who purged his enemies and drove the country’s economy to ruin, Khrushchev said. Given his later role in the crisis over Berlin and Soviet missiles in Cuba, the reckoning with Stalin may well have been Khrushchev’s greatest gift to Russian history. The hardliners, after all, eventually drove him too from power, albeit to comfortable exile and not an early grave.

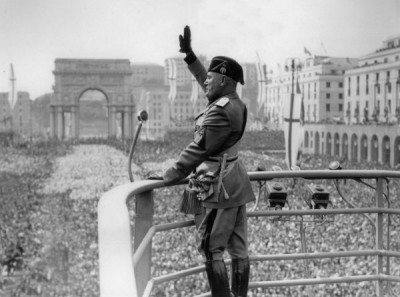

“It was not by accident,” the historian Anne Applebaum wrote this week, that another dictator, Benito Mussolini, “juxtaposed himself against his country’s most famous city squares and most beautiful buildings—the Duomo in Milan, the Colosseum in Rome. He sought to identify himself, physically, with these beloved national symbols, and thus with the nation, and many people loved him for this. Nor were the heavily staged, entirely artificial elements of his performances a mistake. Sophisticated observers such as [the journalist William L.] Shirer sneered, but plenty of people understood that Mussolini was offering theater, putting on a show, acting out a part…That was what they had come to see him do.”

Historians will devote countless paragraphs to assessing the spectacle – the tragedy becoming farce – that befell American life over the last couple of weeks: the Marine One helicopter rides back and forth to the south lawn, the army of white coated doctors outside Walter Reed, the cryptic Stalin-like medical statements lacking all detail and advancing all myth, the slow drive in the closed SUV to allow the great genius to wave to his adoring fans, the Mussolini-like scene on the Truman balcony, the salute, the false assurance that all is well since a great man is in charge.

Truth about powerful men – and the worst of the powerful have all been men – is an important thing, their medical records, their tax returns, their conflicts of interest actually do matter. Great men – and woman – can withstand scrutiny, the con men not so much.

As Tim Miller, who once worked for Jeb Bush and the Republican National Committee, put it: “The show must go on. Where, exactly, the rest of us go from here, I cannot say. What feats Republican senators will be asked to perform alongside Trump to prove their commitment we cannot guess.”

Oh, I’m afraid we can guess. The past is prologue and American democracy is feeling unwell, clearly.

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

Some other reading worth your time…

He was a Crook – The Death of Nixon

I’m not sure how I stumbled on this piece from 1994 by the wildman of new journalism Hunter S. Thompson. It was written for The Atlantic after Richard Nixon’s death. Thompson, let’s say, was not a fan.

“If the right people had been in charge of Nixon’s funeral, his casket would have been launched into one of those open-sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles. He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president. Nixon was so crooked that he needed servants to help him screw his pants on every morning. Even his funeral was illegal. He was queer in the deepest way. His body should have been burned in a trash bin.”

It’s a classic of some sort. Read the whole thing.

Jill Lepore

The historian Jill Lepore has a new book If Then – How One Data Company Invented the Future.

Lepore did a Q and A with The Guardian.

Q. Reading about the extraordinary history of the Simulmatics Corporation and its “People Machine”, it was instructive to see how the anxieties we have today about the more sinister aspects of computer technology were very present 60 years ago. Did that surprise you?

A. “If anything, I think in the 50s and 60s – because so few people had direct experience of computers – there was even more concern than there is now. Computers were associated with vast power. It was only with the arrival in the 1980s and 1990s of the personal computer we were sold the idea that the technology was participatory and liberal. I think we have returned, in a way, to the original fears, now we sense that these personal devices very much represent the power of vast corporations.”

The full piece is here.

F. Scott Fitzgerald for Our Times

I really loved this piece by Ian Prasad Philbrick in The Times about the particular resonance of The Great Gatsby to our present moment.

“They were careless people,” Nick Carraway, the narrator, concludes about Tom and Daisy Buchanan, characters whose excesses ultimately destroy the lives of those around them. “They smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

It really is the Great American Novel. Here is a link to the piece.

The Lincoln Project

A remarkable development of the Trump Era and the current campaign has been the emergence and potentially the influence of a group of Never Trump conservatives who have created various platforms to take the fight to the president. The New Yorker profiled the most prominent group – The Lincoln Project. It’s a great piece for you political junkies. Paige Williams wrote it:

“In 1984, Ronald Reagan framed his reëlection campaign with the ad ‘Morning in America.’ The economy had recovered from a severe recession, and the spot offered dreamy imagery of prospering families. In early May, the Lincoln Project released a dystopian homage: ‘Mourning in America.’ A sonorous male voice-over recalled the narrator of the Reagan video, but the ad showed a grayscape of dilapidated houses, coronavirus patients, and unemployment lines. An American flag flew upside down. Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the author of ‘Packaging the Presidency‘ and the director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, at the University of Pennsylvania, told me that, if the point of the ad was to ‘remind older voters of the difference between what a Republican used to be and what this Republican is, you couldn’t do it more effectively than that.'”

As always, thanks for reading. Stay in touch.