In 1933, during the darkest days of the Great Depression, a Kansas City businessman, Charles Lyon, made a driving tour of the Midwest. Lyon would later write to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and offer his observations. He didn’t like what he saw.

“Every good town had the same stores,” Lyon wrote. “The downtown of one city was a replica of the next one, and for every chain store that reared its head, three individually owned stores laid down and died.”

Lyon’s discourse on the predatory nature of chain stores and their impact on small town America is recounted in a 2008 article by historian Daniel Scroop in the scholarly journal “American Studies.”

“Chain stores pay very little toward the upkeep of a town,” Lyon wrote in the 1930s. “They gradually kill it.”

Remember that line as you contemplate the history of what didn’t happen to slow or eliminate the monopolization of most of American retailing in the last half of the 20th Century. And reflect what it means for your grocery bill when Kroger combines with Albertsons, and together this grocery behemoth – the largest and second largest grocery chains in America – will have more than 6,000 grocery stores spread across the country.

Political and social pushback against the chain store – and branch banking – in the 1920s and 1930s is a mostly a forgotten chapter in 20th Century American history. It is a chapter, nonetheless, that illustrates some of what has happened to small town, rural America, the struggling American middle class, as well as notions about what a healthy, vibrant economy actually includes.

The anti-chain store movement gained traction in the West, Midwest and South during the seemingly prosperous Roaring 20s. The Missouri legislature considered measures to limit chain stores in 1923 and by the end of the decade several states had put various restrictions – mostly tax-related – into effect. The Depression accelerated the movement and by 1937 nearly 30 states had anti-chain store laws on the books.

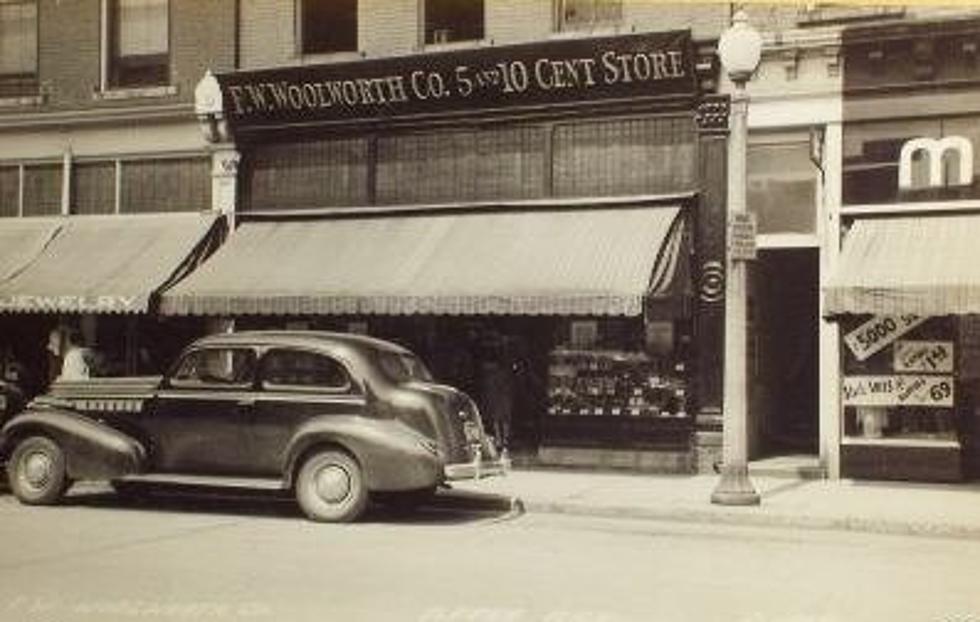

Woolworth’s, the drug store chain, became a target of many of the anti-chain efforts, fueled not only by the vast number of stores the chain developed in the 1930s, but also because of the firm’s brutal efforts to beat back union organizing efforts. Workers in some stores resorted to “sit down strikes” that served to paralyze business and frustrate customers and managers. While the strikes made headlines, they ultimately did little to hinder the constantly expanding development of chain stores.

By the 1940s, the leader of the anti-bigness, pro-consumer, anti-monopoly forces was a crusading congressman from Texas named Wright Patman, a politician who, as his biographer has said, combined two political traditions: populism and liberalism.

Patman pushed legislation to create a national chain store tax where, as historian Scroop wrote, “chains would be taxed from $50 to $1,000 per store depending upon their number and location. Because this figure would then be multiplied by the number of states in which a chain had stores, there was a chance that the tax might in some cases exceed annual profits. If this scale had been applied in 1938, for example, the biggest chain store company, the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P), would have been taxed $524 million on its $882 million in sales.”

This simple idea – taxing bigness – failed, and the anti-chain store crusade, as well as state and local laws to control the monopolies, eventually faded away.

You can see the legacy of this hollowing out and embrace of monopoly bigness in today’s Walmart, Amazon, Costco, Home Depot, CVS, Walgreens and Dollar General, the ubiquitous discounter with nearly 19,000 stores and minimum wage jobs. You’ll almost always find Dollar General stores at the far edge of rural communities that have lost the kinds of home grown retailers that once existed in America’s small towns. The bigness movement also involves newspaper and broadcast consolidation, cable TV systems, hotel chains, even the not so local Taco Bell.

Back to the Kroger-Albertsons mash up which hit a speed bump – maybe – this week when a bipartisan group of state attorney generals called on Albertson’s to back off a planned $4 billion dividend to its shareholder while the $24.6 billion merger deal is evaluated for its anti-trust implications.

Thanks to the AGs for looking out for competition, but you don’t need to be a Harvard-trained economist to know what the merger implications will be – less competition, fewer employees in retail jobs and surely higher prices at the checkout aisle. The dividend payout, the AGs suggest, could hamper Albertson’s ability to compete, weakening Kroger’s merger partner before the merger, which may be the real reason behind handing shareholders an extremely handsome payday just before the deal closes.

“Anticompetitive mergers have real impacts on everyday people,” said District of Columbia attorney general Karl Racine, who organized the AG’s letter. Washington AG Bob Ferguson, a Democrat, and Idaho AG Lawrence Wasden, a Republican, signed the letter directed to the CEO’s of Kroger and Albertsons.

“We’re deeply concerned about the level of concentration in essential industries,” Racine said, “such as grocery stores. And we’re asking Albertsons to not proceed with the payout while we thoroughly assess whether this merger is anti-competitive, anti-consumer or anti-worker. While we trust that Albertsons will adhere to our request, we are actively exploring other options to achieve our objectives, including litigation.”

Here is one of the ironies of these massive mergers: the rationale behind the big getting bigger is that stores like Albertsons need to compete against other huge retailers like Whole Foods or Walmart. Yet advocates of supersizing grocery stores in to fewer and fewer companies, while letting these stores sell gas and virtually everything else, ignores that a largely unconstrained system that demands a capitalism of bigness represents a circular argument – we must get bigger because everyone else is getting bigger.

The ignored parties here are consumer and workers. A growing, robust American capitalism won’t be built around a few CEOs or institutional shareholders getting fabulously wealthy, while much of the rest of society barely scrapes by. Those Woolworth and A&P stories in the 1930s that grew too big in their day have become today’s Kroger and CVS, while the American middle class, the families that buy the groceries, the washing machines, the bedroom sets and the coffee makers struggle to meet a mortgage and send the kids to college.

The big get bigger, the rich get richer, and the engine that really drives the economy – the consumer – is less and less a part of the American economic calculation.

The politicians and social activists in the 1930s who recognized the dangers inherent in concentrated bigness weren’t wrong. We had a chance to build a different kind of capitalism, that we didn’t helps explain a lot about your grocery bill, not to mention the depressed state of much of small town America.

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

A few other items that are worth your time …

The Portland Van Abductions

A deep dive into the Portland street protests in 2020, including the still mysterious “van abductions” by unidentified law enforcement officials.

“The video of Evelyn’s arrest went viral on social media; the account of Mark’s arrest first broke on Oregon Public Broadcasting and was re-reported in the national news.

“The men who took Mark and Evelyn did not identify themselves as federal law enforcement. There are no publicly known records of their arrest or detention. To this day, it’s unclear who took them — what agency they were from, let alone what their names were.”

How World War I Crushed the American Left

I am a huge fan of the historian Adam Hochschild who has a new book American Midnight about how World War I dramatically changed American politics. It looks like a fascinating study.

“The crushing of socialism—and a new bugbear, communism—was total. The treatment of Eugene Debs was a stark illustration of the crackdown. Debs had won 6 percent of the popular vote in 1912, as the Socialists were making gains at the local and state level, threatening both Republicans and Democrats. By 1917, Hochschild notes, there were 23 Socialist mayors in office across the country, leading cities including Toledo, Pasadena, and Milwaukee. Debs opposed the war steadfastly, but he was so widely respected that the government feared directly attacking him. Instead, a disinformation campaign was launched—by whom, historians are still unsure—which implied that he had changed his position.”

Debs went to jail, the very idea of socialism became a third rail of American politics.

A review from The New Republic.

‘A zombie party’: the deepening crisis of conservatism

This piece about conservatism in the United Kingdom is a couple of years old, but it does highlight many issues that dominate modern conservative politics in the UK and in the United States.

“In Britain and the US, once the movement’s most fertile sources of ideas, voters, leaders and governments, a deep crisis of conservatism has been building since the end of the Reagan and Thatcher governments. It is a crisis of competence, of intellectual energy and coherence, of electoral effectiveness, and – perhaps most serious of all – of social relevance.

“This crisis has often been obscured. The collapse of Soviet communism in the 80s, the apparent triumph of capitalism during the 90s, the western left’s own splits, dilemmas and failures, and the ongoing surge of rightwing populism have all helped maintain conservatism’s surface confidence.”

Good piece from The Guardian.

The grand old man and the ingénue queen

I’m admittedly an Anglophile, as fascinated by the mess that is British politics these days as I am appalled by US politics. So … Winston Churchill and the late Queen.

“Winston churchill was besotted with Queen Elizabeth II: the word is precise. He worshipped and adored her. His relations with some other members of the royal family were, on occasion, complicated — not least when King Edward VII was sleeping with his mother. But for the late Queen he had nothing but an almost puppy-dog love.”

That’s all I got. Be safe. Vote like democracy depended upon it – and it does. Thanks for reading.