(NOTE: This is the first of two parts on political spending by independent expenditure committees and how this practice has perverted American politics.)

———-

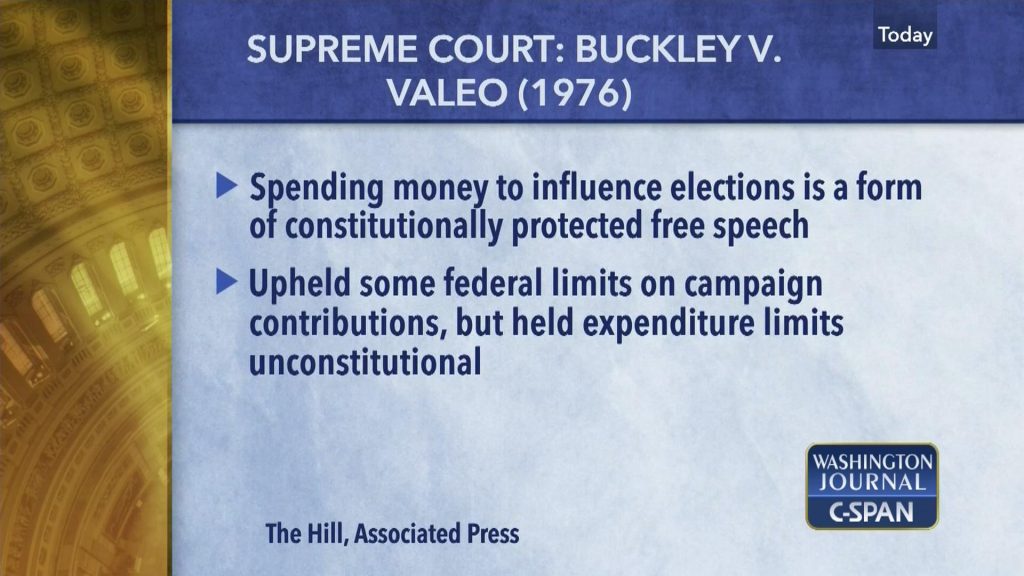

If you were looking to identify a single date in recent history where American democracy made a sharp swerve in the wrong direction, you could do worse than fingering Friday, Jan. 30, 1976. On that day, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned significant parts of the federal campaign finance law put in place in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

To the lasting detriment of rational politics in America, the court held that groups and individuals could raise and spend unlimited amounts on so-called “independent expenditure” campaigns so long as the “independent” groups did not coordinate with a candidate or another campaign.

Not many Americans knew at the time that the decision handed down on that long ago Friday would begin a tumbling of political dominos that would severely distort politics, vastly expand the role of money in politics, breed widespread voter cynicism and lead to a handful of other judicial decisions — the outrageous Citizens United, for instance — that have created a profoundly corrupt system.

If you have come to hate the barrage of “negative” political commercials, the slick mailers and the almost always distorted rhetoric of modern campaigns, you have Buckley v. Valeo to blame. The decision was the foundation stone of modern sleazy campaigns conducted by shadowy groups who employ every measure of deception to hide their donors and their motives.

A landmark 1976 decision

The plaintiffs in the Buckley case were an odd collection of interests, as diverse as the decision was consequential. The Buckley was James L. Buckley, brother of the conservative writer and magazine editor William F. Buckley. Jim Buckley, a Yale Law grad, was a genuine political fluke, elected to the U.S. Senate from New York on the Conservative Party ticket in 1970 with just 39 percent of the vote.

Buckley’s political fluke is owed to his defeat of a Senate incumbent, moderate Republican Charles Goodell, father of current National Football League Commissioner Roger Goodell. Goodell had been appointed to replace Robert Kennedy by then-Gov. Nelson Rockefeller following Kennedy’s assassination in 1968.

Buckley was a one-term senator and later Reagan administration official and federal judge. His name remains, however, most firmly identified with the 1976 court decision.

James L. Buckley a plaintiff in a case challenging federal election law in 1976 that legalized the “independent expenditure” campaign

Two of Buckley’s fellow plaintiffs in suing the Federal Election Commission were liberal Minnesota Sen. Eugene McCarthy, who had made his reputation as the poetry-writing contrarian who helped force Lyndon Johnson out of the presidential race in 1968, and Stewart R. Mott, an eccentric multimillionaire who pumped thousands of dollars into McCarthy’s campaign and other liberal causes. Mott’s support for what a Richard Nixon aide called “radic-lib candidates” earned him a spot on Nixon’s “enemies list.”

McCarthy and Mott had nothing in common ideologically with Buckley, but they all shared an interest in spending lots of money on politics, preferably with as little regulation as possible. The Supreme Court largely sided with them in Buckley, a landmark that one legal analyst called “an exceptional case — a 143-page … behemoth with 178 footnotes, five separate opinions of the eight justices involved, writing eighty-three more pages, which with appendices yielded a 294-page reported decision.”

By the time the Supreme Court decided the subsequent Citizens United case in 2010 — that decision overturned 100 years of settled law by declaring that unlimited corporate and labor union political spending is protected as free speech — Buckley had been cited in more than 2,500 legal cases relating to campaign spending.

To read the decision or listen to the now available tapes of oral arguments is to realize how confused the justices were about the nexus between political money and political corruption. Justice Byron White did understand the linkage and argued that Congress had been correct in identifying a compelling need to limit political money.

Supreme Court Justice Byron White warned against “a mortal danger” involving politics and money

“The act of giving money to political candidates,” White wrote in a dissent, “may have illegal or other undesirable consequences: it may be used to secure the express or tacit understanding that the giver will enjoy political favor if the candidate is elected. Both Congress and this court’s cases have recognized this as a mortal danger against which effective preventive and curative steps must be taken.”

White’s argument did not prevail and, as the Congressional Research Service noted in a 1981 report (updated in 1984) about the subsequent rise of “independent” political action committees, “By lifting the limits on (independent) expenditures, while leaving intact those on direct contributions to candidates, the court’s ruling created a major avenue for individuals and groups seeking to influence elections beyond the level permitted under” federal law.

Before Buckley political action committees (PACs) played a minor role in American politics. Now they are American politics.

For example, one estimate holds that $55 million, much of it from out-of-state interests shielded from disclosure, will be spent on television advertising during the Maine U.S. Senate campaign of Republican Susan Collins and her Democratic challenger.

Maine Republican Susan Collins’ Senate re-election campaign will likely see more than $50 million in spending

Maine is, of course, a key battleground that will help determine which party controls the Senate after 2020. But even given that significance, the Cook Political Report’s Jennifer Duffy calls the $55 million “an astonishing amount for a state with three relatively inexpensive media markets.” Duffy notes that a year before the election, “Democrats have outspent Republicans almost two to one and nearly all that money has been on ads criticizing Collins.”

Outside money, much of it impossible to track, is flooding Iowa’s Senate race and the Republican incumbent, Joni Ernst, has been trying to swat away allegations that an “independent” group helping her and run by some of her former aides has violated the law prohibiting coordination between the candidate and an outside PAC.

Politico reported recently that President Donald Trump is being victimized by an array of groups raising money in his name, but doing with the money God knows what. In an 18 month period, “$46.7 million flowed into close to 20 Trump booster organizations, structured as PACs or political nonprofits and with names like Latinos for the President and MAGA Coalition.”

All this money, of course, is virtually impossible to trace or track, which is after all why we have disclosure. Voters are supposed to be able to see who is supporting a candidate and evaluate for themselves where the money is coming from. But the practical ability to do that is a rude fiction, as is the myth that “independent” committees don’t collude — often very openly — with candidates.

Every Senate race in the country this year will have similar stories to what we’ve already seen in Maine and Iowa because the political money system is broken, unaccountable and, yes, corrupt.

And sadly the corruption is coming to a city hall near you, which is a story for next week.