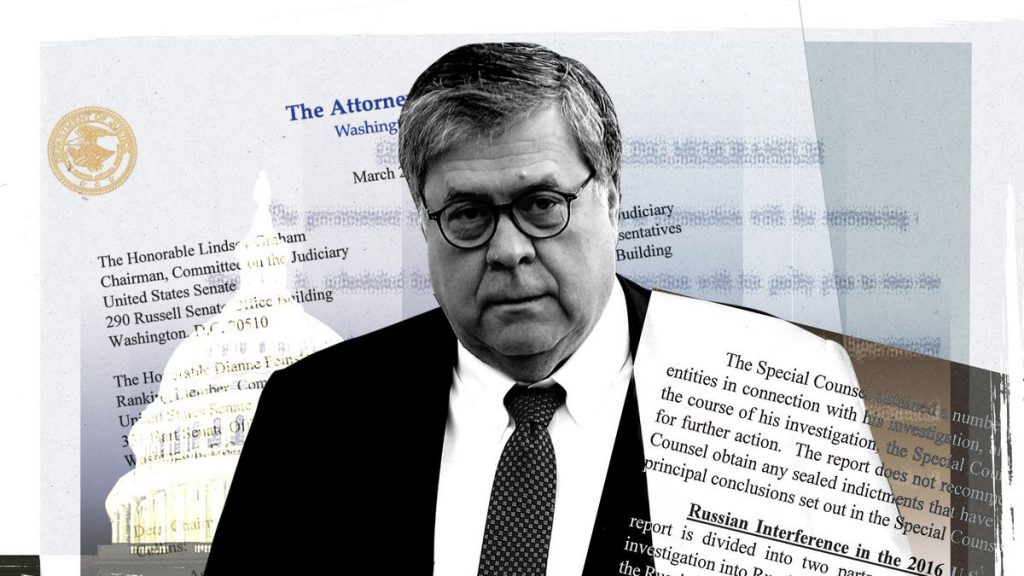

So, the Mueller report is released, but not really released. We have a four-page summary written by a guy who owes his job to the guy who the four-page letter exonerates. And the guy who wrote the four-page letter went into his job having established that the guy who appointed him couldn’t be guilty of obstruction of justice.

We’re told we may eventually see some of the real Mueller report, a document assembled over a two-year period during an investigation that established beyond a reasonable doubt that Russia interfered in an unprecedented way in the 2016 election. That investigation resulted in the indictment or guilty plea from 34 individuals and three companies. Not exactly a run of the mill definition of a “witch hunt,” but we must be very careful says the attorney general (seconded by the Senate Majority Leader) not to tell the public too much about such sensitive matters.

In the last few days we’ve witnessed merely the latest example of the American penchant for secrecy.

Idaho Senator Jim Risch quickly embraced the attorney general’s four-page summary as the definite word on all things Trump and Russia. “For me, there was no news in Mueller’s report,” Risch said in the statement, passing judgment without having seen the actual Mueller report.

“We have reviewed thousands of documents including dozens of witness statements throughout the Senate Intelligence Committee’s investigation, and I reached the same conclusion as Mueller,” Risch says with absolute certainty. “President Trump did not collude with the Russians.” Fair enough, but what about the rest of the report, a document the Justice Department has described as “comprehensive?” The Clift Notes are good for cramming for a test, but real understanding means reading the actual text.

By the way, a poll from Quinnipiac University found that 84% of voters they surveyed think Mueller’s report should be made public, while only 9% disagree.

Despite public support for much greater transparency across the board, Congress routinely joins the Executive branch and defaults to secrecy. Many if not most congressional hearings dealing with Russian involvement in the 2016 election – we are told that Putin-inspired activity remains ongoing – have been conducted behind closed doors. If Attorney General Robert Barr ever manages to get to Capitol Hill to answer questions from our representatives it’s a even bet the questions will be asked in secret and we’ll depend on second, third or fourth hand spinning of the answers from sources granted anonymity in order to, as the saying goes, “discuss sensitive matters.”

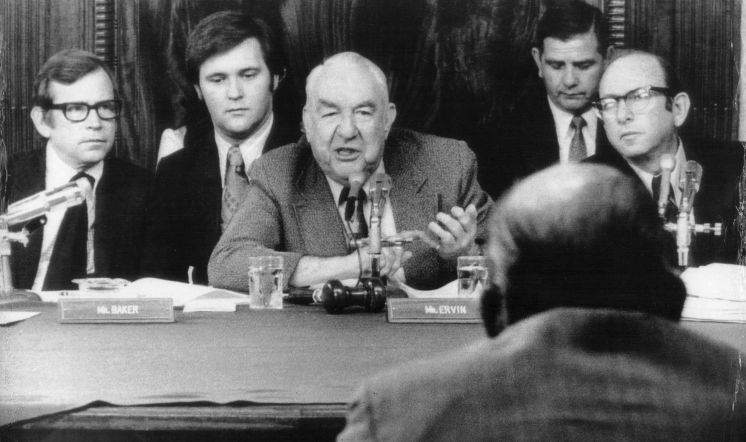

This kind of secrecy rarely happened in the past. The Teapot Dome scandal and the Watergate hearings were held in full public view. The penchant for congressional secrecy has increased in parallel to the penchant for extreme partisanship.

And Laura Rosenberger, who heads the Alliance for Securing Democracy, says transparency might force a bipartisan response that would address the next Russian influence operation. “Addressing Russia’s interference is a matter of national security,” Rosenberger told New York Magazine, “and will require partisanship to be put aside to take real steps to harden our defenses, deter Russia and other countries that might seek to follow suit, and build societal resilience.”

More secrecy, she says, “would play directly into Putin’s hands.”

The intelligence agencies are among the worst at overdoing secrecy and the congressional committees overseeing the agencies now routinely aid and abet the lack of transparency. We are assured that every thing is under control, while a senator bent on secrecy in service to partisanship can conveniently say – Risch does this all the time – that he has secret information that proves his partisan position.

The National Security Agency (NSA), one of the worst of the secret keepers, was, as Conor Friedersdorf has written, “maximally secretive from the start: President Truman created the NSA with the stroke of a pen at the bottom of a classified 7-page memorandum. Even the name was initially classified. Decades later, the memorandum that acted as the agency’s charter remained secret. Reflect on that for a moment. In a representative democracy, the executive branch secretly created a new federal agency and vested it with extraordinary powers. Even the document setting forth those powers was suppressed.”

Some things are so secret we can’t even admit they exist. NSA, it’s often been said, really stands for “No Such Agency.”

The Idaho Legislature is hardly immune from this epidemic of government by secrecy. Lawmakers have been debating legislation that would essentially do away with the ability of citizens to place an issue on the ballot and the origins of the awful idea to gut the initiative process has in no way seen the light of day. Increasingly what happens in public view during the lawmaking process is pro forma, developed and rehearsed in a back room and sanctified in public procedures that appear to include citizens, but really only involves the public as a prop in the process.

How else to explain the legislature’s headlong rush to destroy the initiative in the face of overwhelming public opposition? This whole smarmy mess was birthed in secret, hatched by lobbyists over lunch. It brings to mind Art Buchwald’s observation about where real political power resides. “Lunch is the power meal in Washington, D.C.,” Buchwald wrote, “it’s over lunch that the taxpayer gets screwed.”

Government secrecy is endemic, but even more it’s dangerous. As Frederick A.O. Schwartz has written – he was the chief counsel for the Senate Committee that investigated the intelligence agencies, the Church Committee – we need to understand the cost of all this secrecy.

“Too much is kept secret,” Schwartz wrote in his book Democracy in the Dark, “not to protect America but to keep embarrassing or illegal conduct from Americans.”

And while we’re thinking about secrecy, ask yourself what the last two years might have been had a certain political figure accepted the tradition that has existed since Richard Nixon, a tradition now shattered, of a president being transparent about his tax returns?

—–0—–

(This piece originally appeared on March 29, 2019 in the Lewiston, Idaho Tribune.)