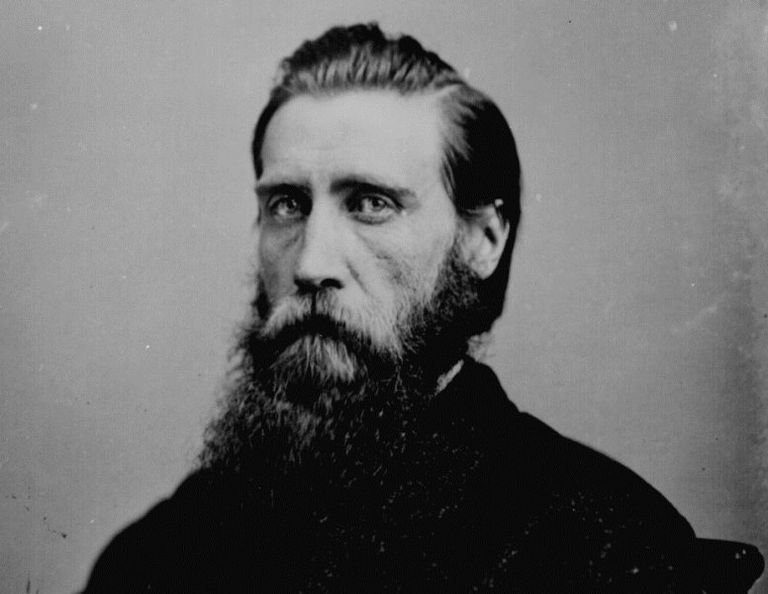

On November 30, 1864 the Civil War in what was considered the western theater effectively ended. After the bloody battle at Franklin, Tennessee, Confederate General John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee literally ceased to exist as a fighting force.

Bell, a Kentuckian and West Point graduate, wrecked his rebel army by smashing it against the breastworks of the army of the United States against which he was in rebellion. The frontal assaults ordered by Hood, who was by all accounts himself a very brave man, severely wounded in earlier battles, left the field strewn with southern dead.

“Never in any single-day battle during the entire war had that many Confederates soldiers been slain,” the historian and novelist Winston Groom has written of the Battle of Franklin. “In fact, Hood’s losses were double those of George Pickett’s famed charge at the height of the Gettysburg campaign. To add to the misery quotient, on no single-day battlefield of the war had so many generals been killed.”

And yet this is the soldier – a traitor to his nation, a brave but thoroughly reckless man when it came to the lives of his soldiers – that our country celebrates by putting his name on the largest military base in the country for training armored units of the U.S. Army.

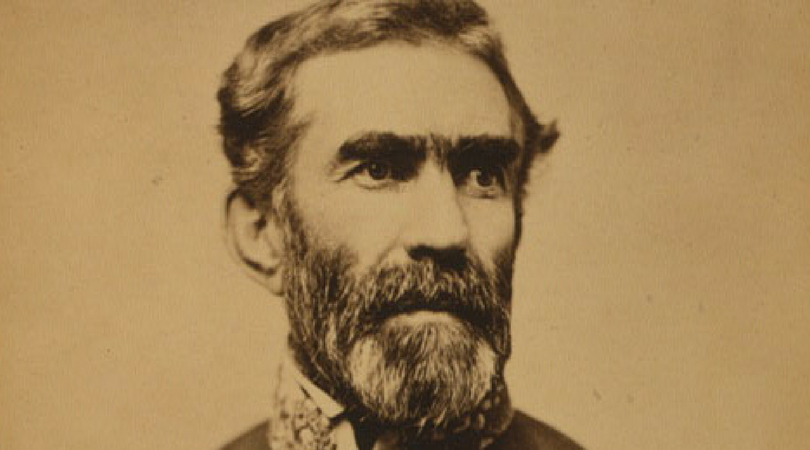

By general agreement among Civil War historians Confederate General Braxton Bragg, a North Carolinian, was among the very worst generals on either side. As historian Peter Cozzens has written, “Even Bragg’s staunchest supporters admonished him for his quick temper, general irritability, and tendency to wound innocent men with barbs thrown during his frequent fits of anger.” In short Bragg was a disaster as a military leader, not to mention a traitor to his country.

Yet this man was honored in 1918 when his name was attached to what is now Fort Bragg, North Carolina, home of the Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps of which the legendary 82nd Airborne Division is a part.

Fort Benning in Georgia is named for Henry Lewis Benning, a mediocre Civil War general, but a world class racist even by the standards of his time. As the New York Times noted recently, “Benning warned…that the abolition of slavery would one day lead to the horror of ‘black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything.’”

Fort Polk in Louisiana is named for a West Point graduate, Leonidas Polk, who resigned his commission to become an Episcopal priest. His political connections, particularly his friendship with Confederate president Jefferson Davis, led to a general’s commission during the Civil War. Deficient as a battlefield commander, Polk also made an awful priest. He made it his task to use religion to justify owning his slaves. Polk’s military service is perhaps best remembered for his bitter quarrels with Bragg. The two hated each other and richly deserved each other.

All total ten different U.S. Army bases are named for Confederates who not only took up arms against their country thereby violating their Constitutional oath as officers, but who also fought to preserve slavery.

The American Civil War, at least until the Trump presidency, was our great national tragedy, but the losers of the conflict succeeded in remarkable ways in writing the narrative of the tragedy. The United Daughters of the Confederacy helped perpetuated the myth of The Lost Cause, the fiction that the Confederate cause was noble and its leaders chivalrous, by erecting in the early 20th Century most of the statutes and monuments that lately have been coming down.

Georgia born Margaret Mitchell cemented The Lost Cause myth in American culture with the publication of Gone With the Wind in 1936. The book remains an all-time best seller, but neither it nor the movie with its sanitized portrayal of a fight to preserve slavery, are history. Mitchell, as the novelist Pat Conroy wrote, “was a partisan of the first rank and there never has been a defense of the plantation South so implacable in its cold righteousness or its resolute belief that the wrong side had surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse.”

The myth making, including the Confederate monuments and the misnamed military bases, has never been more under attack than it is right now. And it’s about time. As historian Gary Gallagher, one of the great exposers of the myths of the Civil War, often notes, the terrible conflict wasn’t about some abstract notion of state’s rights or preserving a “southern way of life.” Our Civil War was fundamentally about the “peculiar institution” of human slavery. “One of the things that scared Confederates the most,” Gallagher says, “was that defeat would mean the loss of slavery and thus their control of black people.”

(Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

The president of the United States, of course, doesn’t read history and understands it not at all. So, he declares “Our history as the Greatest Nation in the World will not be tampered with. Respect our Military!,” and thereby rejects the removal of names of treasonous racists from ten U.S. military bases. But Donald Trump and all who cling to the gauzy legends are choosing not to reflect the reality of American history, but to revere the myths of it.

“We cannot be afraid of our truth,” then New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu said in 2015 when he declared that his city’s legacy of reverence for the traitor class that sought to destroy the United States was over. It has never been more important to confront our truth.

And while we’re at it how about Fort Gavin to replace Fort Bragg in honor of General James Gavin who jumped with his 82nd Airborne into Normandy in 1944 and later became a critic of American policy in Southeast Asia. Gavin’s wartime decorations included the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Cross and the Purple Heart. A true American hero. There are many others vastly more deserving than Hood or Benning or Polk.

Michelle Alexander, who wrote a searching book about civil rights and our history called The New Jim Crow, says “It’s not enough to learn the broad outlines of this history. Only by pausing long enough to study the cycles of oppression and resistance does it become clear that simply being a good person or not wishing black people any harm is not sufficient.”

A start at greater sufficiency at this moment of reckoning over history and racism would be white folks acknowledging that the symbols of oppression and the names of those that oppressed should not be glorified.

—–0—–

Additional Reading:

We Never Learn

UC Berkeley law professor Frank Partnoy writes in the current issue of The Atlantic about something most of us have probably never heard of – the CLO, or collateralized loan obligation. His article is entitled “The Looming Bank Collapse” and paints the worst of worse case scenarios about the financial sector that Partnoy says could make the 2008 banking crisis look like a walk in the park.

“The financial sector isn’t like other sectors. If it fails, fundamental aspects of modern life could fail with it. We could lose the ability to get loans to buy a house or a car, or to pay for college. Without reliable credit, many Americans might struggle to pay for their daily needs. This is why, in 2008, then–Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson went so far as to get down on one knee to beg Nancy Pelosi for her help sparing the system. He understood the alternative.”

You should read the whole thing and then discuss whether to put some cash under the mattress.

Bolton Settles Scores

The New York Times ran a brutal review of The Room Where It Happened, the new tome by former national security advisor John Bolton.

There are a lot of great lines, including reviewer Jennifer Szalai description of Bolton as a “lavishly bewhiskered figure whose wonkishness and warmongering can make him seem like an unlikely hybrid of Ned Flanders and Yosemite Sam.” Spoiler: She didn’t like the book.

And Susan Glasser in The New Yorker has a good piece here about the book and the author. She writes: “Bolton mocks, disparages, or clashes with Steven Mnuchin, Nikki Haley, Rex Tillerson, James Mattis, Mike Pompeo, and others, all within the book’s first hundred pages. By the end of the nearly five-hundred-page book, Bolton also criticizes Mick Mulvaney, Jared Kushner, the entire White House economic team, many of his foreign counterparts, and, although he shares their misgivings about Trump, the House Democrats who impeached the President.”

See, now you don’t have to read the book.

Biden’s VP

I have no idea who Joe Biden is going to pick as his running mate and Jonathan V. Last admits to the same, but he received some amazing insight from a guy who is a professional gambler. Believe me it’s worth reading, even if you aren’t a political junkie.

Thanks for reading. And stay safe.